Will Schwalbe's "We Should Not Be Friends" Is About His 40-Year Bond With a (Sensitive) Straight Jock

The NYC author of "The End of Your Life Book Club," about reading with his mom as she was dying, has a new memoir—a launching point for our talk about the role of friendships in the gay life cycle.

Happy February, Caftan readers! I am so happy to be “back here” (in the digital ether) with you. And I am always grateful for your support. A goal of mine this year is to post perhaps more than once a month—maybe, say, the usual long interview but then a shorter one or two, or a post highlighting some cool piece of ephemera I found, or—oh, I don’t know! We’ll see if I manage to, amid my other assignments and trying to finish a new novel. As it is, I’m trying to work out the interview for March!

Lately, I’ve been keeping a journal for the first time in my life since the mid-late 90s. I started thinking about all the intervening years where I can’t remember what I actually did on a daily basis, who I saw, where we went, what we talked about. So much living, and now all of it’s just a blur! So I decided to start keeping a log again, if only so that I can remember my life on a daily basis in the years (hopefully!) far down the road. My entries are usually short and to the point—just a few lines, with very sparing commentary. But interestingly keeping the journal has had the effect of putting me more in touch on a daily basis with a sense of gratitude for my life—which, admittedly, on a typical weekday can be a lonely grind of laptop work and perhaps a trip to the gym. Now, though, when I come home and make a note about having had dinner with a certain friend or group of friends, or having seen a certain movie or play or what have you, I have this more vivid sense of the importance of living life to the fullest—of not merely letting days slip by in a kind of monotonous haze. It’s interesting! I highly recommend it.

Oh! One more thing…what do you think of my new author photo? It was taken by my talented photographer friend Eric McNatt.

It’s for my novel Speech Team, which isn’t coming out until August but already is getting pre-pub reviews on Goodreads from people who have access to a digital copy (somehow), which is rather weird.

Anyway, my interview this month is with longtime NYC book writer and editor Will Schwalbe. Have you heard of him? For one thing, he’s the longtime editor of novelist Andrew Holleran, whom I interviewed a few months ago. (In fact, Andrew is the only fiction writer Will still edits at this point.)

He’s also the author of the very successful The End of Your Life Book Club, his memoir about all the books he read with his mother more than a decade ago when she was dying of cancer.

He’s also written Books for Living and coauthored with David Shipley Send, a book about email etiquette.

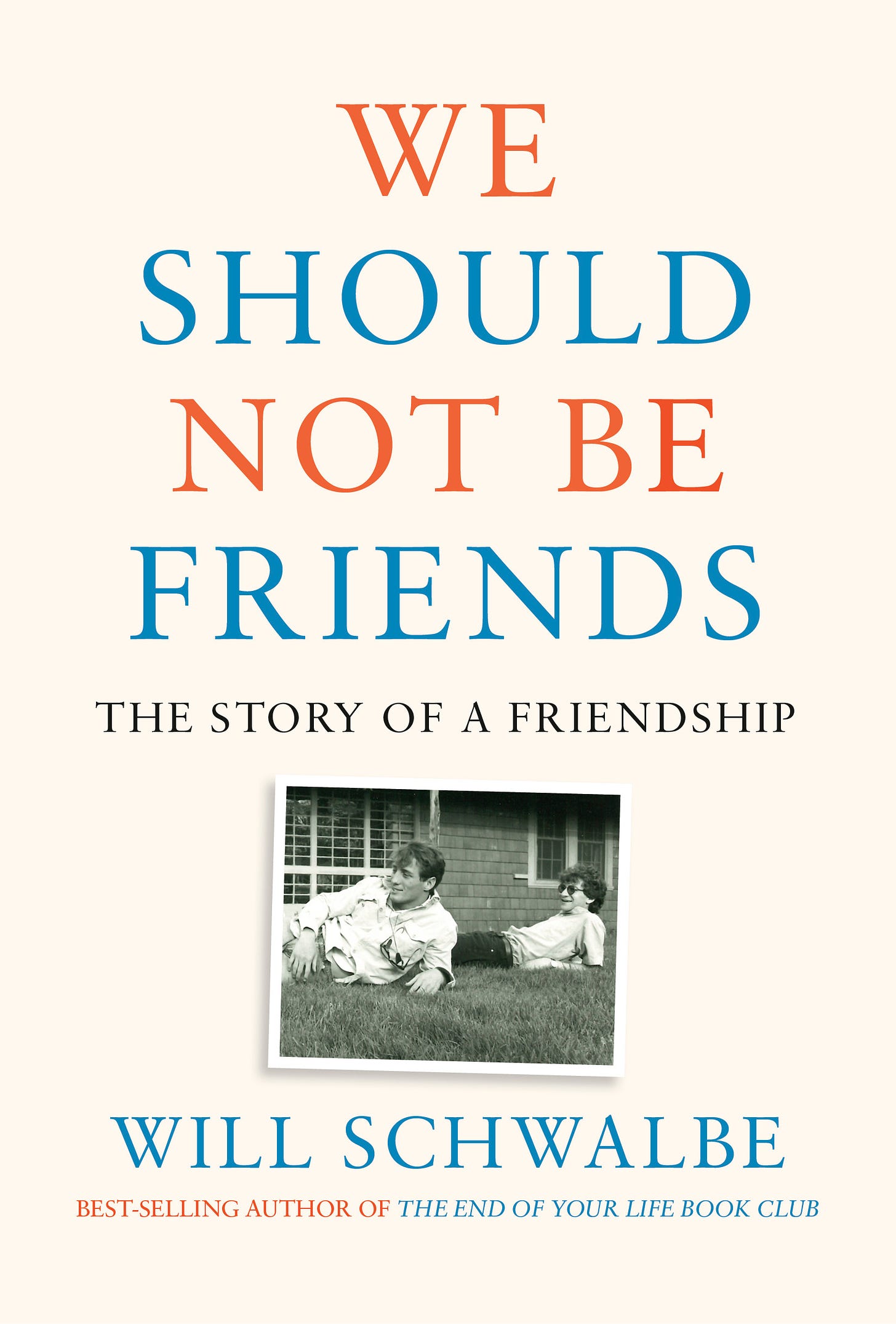

But our interview was primarily to talk about his brand new memoir We Should Not Be Friends, which is his account of his now forty-year bond with a straight guy he went to Yale with, Chris Maxey, whom everyone just calls Maxey.

“They should not be friends,” Will tells himself when they first meet as members of one of Yale’s elite secret societies in the early eighties, because they’re so different—Maxey is a big loud swaggering jock who affably insults friends by calling them “You homo”…

…while young Will is bookish with a precocious sense of gay activism (not to mention a precocious gay sex life).

But the book is about how, somehow, they not only stay friends over the course of many years but become ever closer as they both go through life tribulations—particularly severe illness on both their parts, chronic on Will’s part—and as they (particularly Will) learn to stop putting up a front of “I’m great!” and become vulnerable to each other with their deepest secrets and fears. It’s quite moving.

I have a best straight friend from college myself, Mr. Jeff G., and even though he’s not remotely like Maxey, I identified with Will’s book in the sense of having this friendship that perhaps should not have sustained itself because of our separate paths—for Jeff, marriage and two kids; for me, one messy relationship after another—but somehow did, amid many rocky chapters on both our parts, and became closer over time.

Will gave me a really good interview—I particularly loved talking with him about writers and books, our shared passion, and he named some titles I’m not familiar with and want to check out. Will has been in a nearly 40-year relationship with his husband, and I’d wished he’d been willing to talk about its inner life, including the sexual side, a bit more, but he said he was very private about his relationship, so that’s that! Understandable! I’m always grateful for whatever somebody wants to share about their life.

So folks, here is Caftan’s February interview—Will Schwalbe. Enjoy! Cross your fingers that someone interesting comes through for March! Always happy chatting with you and always grateful for your support. Tim

Tim: Hi, Will! Thanks for being my February Caftan interviewee. Congrats on the recent publication of We Should Not Be Friends. One thing that's so striking about the book is the detail and coherence with which you remember whole conversations. How did you do that? Have you kept a journal all these years?

Will: I don't know how closely this technique matches other memoirists, but I thought very deeply about what I guessed I'd said at certain moments. In this case, I had the ability to do this with Maxey, so we spent countless hours saying, "When I talked to you about that thing I think I said...is that how you remember it?" And he'd be like, "Yeah, yeah, exactly..." And I'd say, "I think you said..." We used both our memories. Also, whenever I'd had a conversation with someone still living, I'd send them the dialogue and say, "This is how I recall it. Is it how you recall it?" I wanted to get the spirit, if not the exact words, right as the participants recalled it.

But I do have a lot in my diary, and Maxey also gave me his journal, where he wrote a lot of dialogue contemporaneous with when he had it.

Tim: So how did this book come into being? How did you get the idea for it?

Will: I did the memoir about my mom, then Books for Living and Send (with David Shipley; about email etiquette). But over the last several years, I'd been saying to Maxey that his life was so interesting—to go from being a Navy SEAL to starting this school [in the Bahamas, with an and becoming an environmentalist—that he should do a book. He liked the idea and wrote some stuff I thought was good and interesting, but then he told me that he didn't have time to continue, that he had four kids and was running a school in the Bahamas. So I asked him to write a book proposal and said that maybe I could find someone to help him, and he said okay. But one night I thought, "I wanna do it." So I told him I wanted to write his biography, and he was like "Sure, whatever you think." He's very modest.

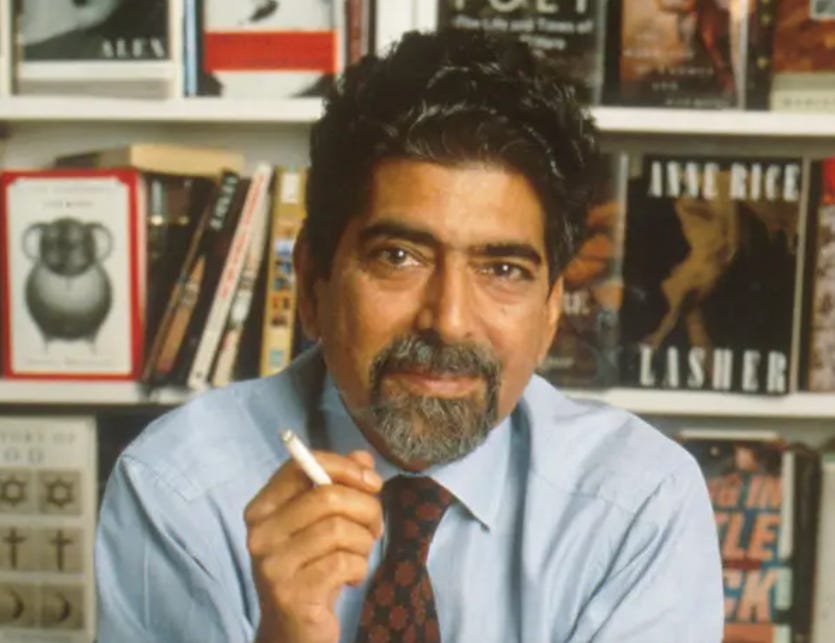

So I wrote a proposal and sent it to Sonny Mehta [the legendary longtime editor in chief of Knopf, who died in 2019] and [Knopf editor] Dan Frank.

We all had lunch. Sonny was famous for his incredibly long silences in conversations, and he was silent a long time. Then he said, "I think the book you really want to write is about your friendship." And the minute he said it, I knew he was right.

Tim: So how would you boil down your friendship with Maxey? What was the main dynamic?

Will: When I first met him, I thought he was a loud, obnoxious frat boy jock asshole. Jocks moved in packs. Twelve of them would enter the dining hall from wrestling or rugby, a mass of chest-thumping loudness. That scared me. I gave them a wide berth. And Maxey had all those characteristics. I thought he was prejudiced against me, and he probably was, but I was far more prejudiced against him. I made a lot of assumptions about who he was in his heart that I had no evidence of. It was about his being loud and who he hung out with.

Tim: But what would you say was the whole arc of the friendship, why you wanted to write a whole book about it?

Will: That I took an instant dislike to him and assumed he did the same of me, because we were different. I was a gay activist. But then we started to like each other and become friends, then the friendship fell apart when I heard him say [jokingly to somebody else] "You homo." But I decided to give him another chance, and over the course of the next 40 years, we repeatedly found and lost each other, and both found and lost ourselves. But whenever we got together, not only did we pick up where we left off but our friendship deepened, and over time we realized we had a very profound friendship and just wanted to spend time together. It's the kind of story that could only be told after 40 years.

Tim: What do you want people to take away from the book?

Will: That we can be friends with far more people than we might have thought. It's very common to make assumptions about who can be our friend based on superficial things. I'm not saying I believe everyone can be friends—this is not a kumbaya book. But in our friendship, we discovered that we had the same values.

Tim: Like what?

Will: It's hard to put into words. The way you treat your friends, and not lying, cheating and being cruel to people.

Tim: When do you think you most opened up to him in a way you never had before?

Will: One of the key things in the book is the role that reunions played in our lives. At our Yale reunions, we'd meet on the roof of our secret society [this is a thing at Yale] and fell into this pattern of going really deeply into our lives. It's where I opened up about being a mess, having a failing business, my mother dying, putting on weight. It hearkened back to a moment before we graduated where we were on the roof and both didn't know where we were going with our lives and confided our fears to each other, that we were both so privileged and terrified that we were going to blow it. That's when the seeds of our true friendship were planted.

Tim: One interesting thing about the book is that, despite the gay versus straight stereotypes, Maxey actually seems to me to emerge as the warmer and more emotionally courageous of the two of you. Would you agree?

Will: One-hundred percent. He let himself be more vulnerable and came to me in moments of doubt. He gave me the gift of allowing me to be helpful. I suffered from Best Little Boy in the World syndrome, these ideas about the armor we put on as gay boys growing up: never be vulnerable or show your weakness, try to sail through life as this little helper who never needs anything. I was selfish with my problems and didn't share with him.

Tim: Do you think that's partly because you resented his straight privilege?

Will: No. I'd always had a very tight circle of straight friends, some of whom were talented athletes like Maxey, but what made my friendship with him so unusual was that he seemed like another species to me—like he came from another planet.

Tim: But you never on some level resented his not having to navigate himself as carefully in the world as you did as a gay man? Don't you think that accounted for some of his bravado and taking up space?

Will: I felt the injustice of what we as gay people needed to go through and I did feel that intensely about the straight world—but I always excluded my straight friends from that. It bothered me on a societal level but not an individual one. I just wasn't wired that way. I was extremely angry about the way gay people were treated in the world. I still am. But in the seventies, there were specific ways in which it was worse than it is today. St. Paul's, the boarding school I went to, never had an out gay teacher or student when I was there. I actually came out to a theater friend, a girl, who said to me, "You can't tell anybody about this or you'll have to leave the school."

But I had another friend, a handsome sweet guy from San Francisco who I thought might be gay. So at a graduation party I told him and he was like, "That's cool," and then he wandered away and I saw him talking to clumps of people. He came back and I asked, "Did you just tell everyone I'm gay?" and he was like, "Yep." I said, "Oh my God—why?" He said, "I thought you wanted me to." And I said, "You know? I did! Thank you! I'm out! I'm free!" I knew in a couple of hours though I'd never see any of them again. This was 1980.

Tim: Wow—thanks for the discretion, friend! So, has Maxey read the book?

Will: He loved it. He read it many times in many stages, and I gave him carte blanche to take out anything he wanted, no questions asked. Our friendship is more important than the book.

Tim: Has the book changed the friendship?

Will: Happily not. I'm a worrier. I worry about everything—choosing the right restaurant, the tone of an email. Maxey just isn't that way. He's a very strong, confident person, very caring. Working on this was fun. We spent hundreds of hours talking. We rewrote some lost letters we had to recreate. And he retold me his Navy SEAL stories.

Tim: One thing that struck me was that you make much of how different you and Maxey were—he the boisterous jock, you the brainy queer—but in fact you both came from extremely elite, overwhelmingly white boarding school backgrounds. I mean, were you really that different?

Will: Even in college, we recognized how incredibly similar we were in so many ways with our privileged upbringings and prep schools. And yet there were things in the culture that made us seemingly totally incompatible and living on different planets.