Andrew Holleran's "Dancer from the Dance" Was Just The Beginning. "The Kingdom of Sand" Is His Latest.

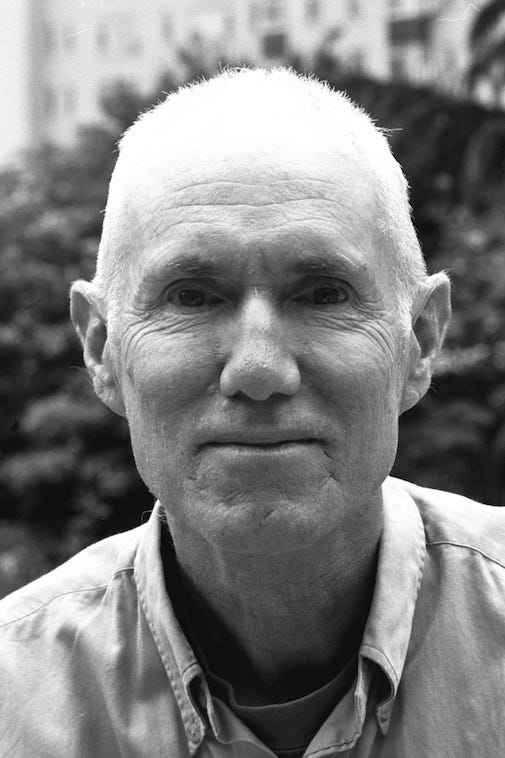

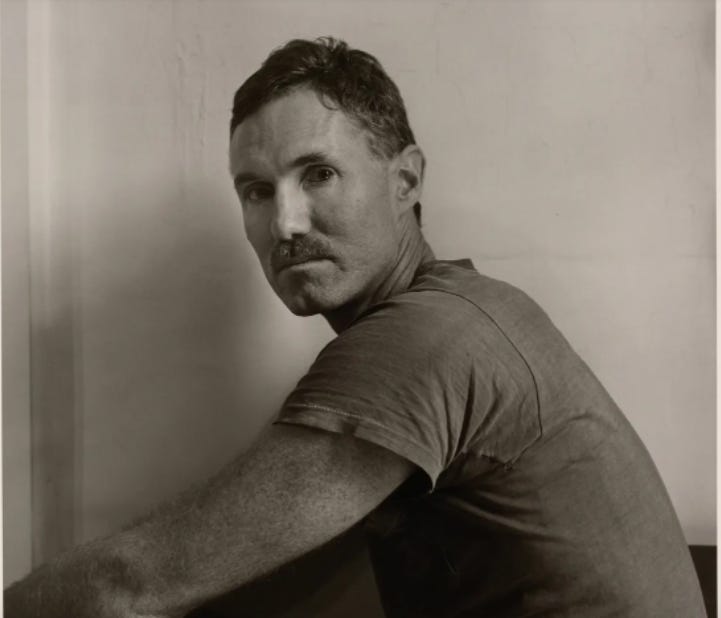

Now 79, America's most elegiac living gay writer is back with his first novel in 16 years, an unbearably beautiful (and...funny!) aria of old age, loneliness and loss.

Happy Pride Month—June 2022—Caftan Chronicle readers!

I do hope everyone has been well. I want to say again how thankful I am for both the paid and unpaid subscribers to Caftan - you help keep this labor of love of mine alive! So please consider subscribing at $5/month if you don’t already, and/or telling folk about Caftan over your social or email. Oh, and did I mention in my last iterations that I have a new novel coming out next summer from Viking? It’s called Speech Team and it’s probably the most autobiographical thing I’ve written since my first novel, Getting Off Clean, which I wrote in my twenties. I hope it’s a ripping good read that will make you laugh and cry. I certainly wrote it to be that.

Speaking of novels, I am so excited about this month’s interview. It’s with one of the greatest living gay American novelists—IMHO, frankly, simply one of the greatest living American novelists, gay or otherwise. For years, I’ve been enthralled and sent into raptures or tears of romance by his lush, lyrical prose, so luxuriantly melancholy yet also suffused with a mordant, campy wit—often in the old-school high style.

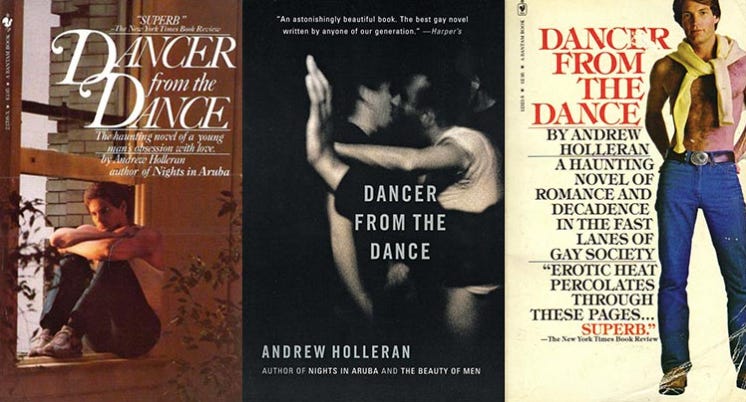

I’m talking, of course, about Andrew Holleran, author of the iconic 1978 Dancer from the Dance, often called the greatest gay American novel ever written and sometimes compared to The Great Gatsby in its gorgeous evocation of the glittering hedonism—and spiritual emptiness—of a particular group of people in a particular place and time. That would be the 1970s NYC gay A-list disco/Fire Island underground versus the 1920s country-house smart set.

In fact, before I go any further, let me give you a little playlist of some of the early-70s pre-disco bangers that come up again and again in Dancer:

>The Temptations, “Law of the Land”

> The Intruders, “I’ll Always Love My Mama”

>Patti Jo, “Make Me Believe in You” (This track, by Curtis Mayfield, and mentioned several times in the novel, has one of the most thrilling intros I’ve ever heard.)

>Barrabas, “Woman”

>Zulema, “Giving Up”

>Clara Lewis, “Needing You”

>The Stylistics, “One-Night Affair”

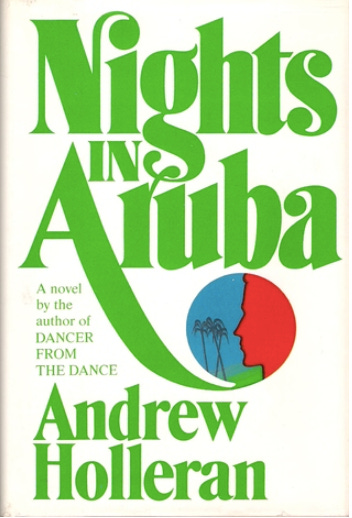

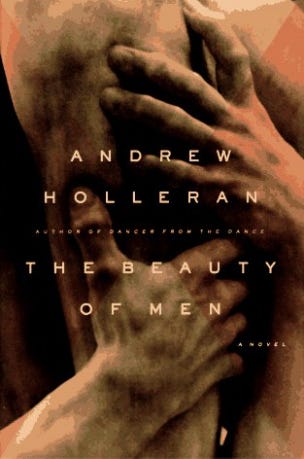

Many people don’t know that Holleran published three novels after Dancer—1983’s Nights in Aruba, 1996’s The Beauty of Men and 2006’s Grief—as well as the 1988 essay collection Ground Zero, heavily informed by AIDS’ toll on his world and circle of friends—and the 1999 story collection In September the Light Changes, which, as I write this, is the only thing in the Holleran oeuvre I’ve yet to read. (But I will this summer!)

As for all the other works, and as a writer myself, I can barely begin to articulate what I love so much about Andrew’s work. The prose is so lush, the descriptions of both the urban and the natural world so impossibly vivid and suffused with emotion. Andrew has an ability to keep you turning those pages, even while there’s very little of what you would call conventional plot, because you are so entirely in the head and the world of his narrators, which are all inflated versions of himself. Holleran is autofiction, artful diary-keeping at the highest level, very much a successor to Proust and Duras and a precursor to contemporary darlings like Karl Ove Knausgard, Rachel Cusk and Sheila Heti.

But I think what I find most riveting about Holleran’s writing—like a car wreck I cannot look away from—is its unflinching, almost perverse, exploration of loneliness, abjectness, shame, desperation, rejection, aging and loss. That’s enough to make you run away, isn’t it? I get it. And yet Andrew leans so hard, almost luxuriantly, into these themes that, as a reader, I feel I almost come out the other side, past my own fear of loneliness, aging and death. And yet I say almost. Because, often, his novels suffuse me with terror as to how my—our—lives could turn out. And yet they also offer those glimpses of beauty—often in the natural world, such as the color of the sky at sundown, or simply of the lifeline of a single friendship—that suggest one could go on living, even with a modicum of happiness, in the face of loneliness, old age and death.

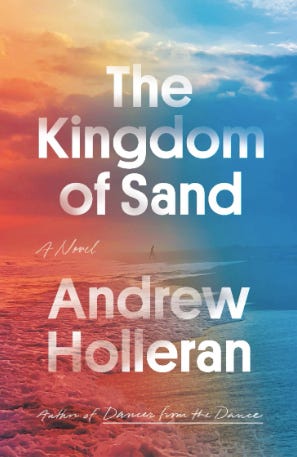

Andrew now has a new novel, The Kingdom of Sand, his first in 16 years.

I can’t tell you how this book tore me up. This is Holleran at 79, the closest to death’s door his fictional avatars have ever been. The isolation and aura of senescence and decline in this book is almost unbearable. It feels as though it could be the closing chapter on a theme Holleran has chewed on since Dancer from the Dance—which is how gay men, particularly of a certain generation, find love and meaning as they age when they usually have no children of their own and, often, no partners either. They do, often, have friendships, however, and friendship occupies a poignant, though hardly idealized, place in The Kingdom of Sand.

Each of Andrew’s novels since Dancer have become more focused on these themes, with his latest seeming to be a culmination. How could he go any further into the realm of decrepitude and obsolescence? And yet it almost seems as though, after some of the starkness in his writing that appeared during and after the plague years, Holleran’s lyricism—the sheer beauty of his descriptions of the everyday natural and built world—has returned full throttle.

So when I say that this new novel destroyed me, I mean it in the best way. As a writer myself, I find that Holleran is the kind of writer who makes me want to be better—to wring magic and transcendence from words, because he seems to do it so effortlessly.

On May 27, Andrew talked to me on the phone for an insane two and a half hours from the small town in northern Florida where he’s spent much of his time since leaving New York City in 1983 to care for his now-deceased mother after she had an accident. (He’s also lived much of the past several decades in D.C., teaching fiction at American University, and Grief is set there, making it one of the few American novels to depict this most bureaucratic of cities in such poetic and elegiac terms.) We’d actually emailed for several months before, with me every time trying to convince him to do this interview by remarking on his work in what I hoped was the most thoughtful and insightful manner possible.

And then we finally spoke. Andrew, to me, has the air of a very well-bred salon hostess of years past—a joyously robust laugh, a damning talent for turning the interview around on his interviewer—how could I resist when he’d constantly ask, “What do you think of that? What do you make of that?”—and a supreme gift, well-reflected in his novels’ dialogue, for delivering shade in the most delicately oblique manner. I adored him. I rarely say this, but I am truly so honored he agreed to talk. So here we go! And please put The Kingdom of Sand on your summer reading list. It’s rare when we are invited to look at decline and death through such a luminous lens.

Tim: Andrew, I cannot believe we are finally talking. I am truly so honored. Can I start by asking what you do or do not like in an interview, as I know you’ve done your share over the years?

Andrew: I’ve never thought about that because I feel an interview is something one just has to do without complaining. (Laughs uproariously.) That you're lucky to be interviewed, so shut up. But if you ask me a stupid question, I'll scream. On the other hand, I'll say "That's such a good question" if you ask one. I'm already fascinated to learn that 1974 is the year you would go back to in New York City if you could go back to just one year. [I had told him this while we were breaking the ice and chatting before the interview proper began.] The 1970s in New York has assumed this romantic aura. The weirdest thing about growing old is watching ordinary people like Larry Kramer [who died in 2020] become these figures—when, to you, they were just people.

Tim: Do you have 1970s nostalgia now?

Andrew: Yeah, I do. You said you moved to NYC in 1991, yes? [Me: Yes.] And you said you were nostalgic for the 90s, which to me is amazing that you could be nostalgic for that pre-cocktail time, the worst years of AIDS.

Tim: I don't think we ever feel we are living in a zeitgeist moment, but we remember it as such, partly because we were young then and hopefully living these wild lives, going out day and night. And also because I was just moving here in the 1990s out of college, I didn’t have many friends living with HIV or AIDS, and I had not lived through the darkness of gay life in the 1980s in the city.

Andrew: The one person in the 1970s who actually did say at the time that it was an extraordinary golden age was [novelist] Felice Picano. I was very skeptical. I thought he was just being gay-proud, claiming something for gay people that I thought was over the top. But looking back, I think he was right. A remarkable confluence of things happened in the early 70s. But I also realized at some point that you should only stay in a city for five years, and this was true for me in D.C. too, because those are the years you are discovering things. For me, that moment in NYC was when I was no longer getting lost on the subway. Proust said that habit is what we use to kill life, anesthesize ourselves. That's true, but I love habit and order. But you realize you're paying the price of no longer being shocked. And for me, my first five years in NYC [1971-76] were a discovery period. I didn't know my friends yet and had a lot of loneliness walking around by myself. But it was magic for the same reason.

Tim: Oh, that's very interesting. I've lived in NYC for 31 years now and I see it more as different chapters that layer one over the other, like a palimpsest. But anyway, one thing I wanted to ask you was whether you outline your books, because they are relatively plotless yet they all have this beautiful kind of movement to them. On an emotional level, they are going places.

Andrew: Well thank you, but I feel the lack of plot in my books is a drawback. I don't design or outline them. I'm in awe of writers who say they knew just what they were doing, that they deliberately withheld certain things to reveal them later. I admire design so much but I just don't have it. I start with the first line and somehow the thing keeps going. When I do think of writing a plot, I cringe and step back. It's too obvious. But really I wish I could. Take [gay British novelist, often compared to Holleran] Alan Hollinghurst, whose books are so well structured. You finish them and say, "Well, that's a writer." Even Proust goes on for 3,000 pages and yet in the middle, he'll say "We will later learn..." And you realize he's saving something for later! [laughs incredulously]

Don't you think that no writer has all the gifts but is strong only on certain things? Except for maybe Gatsby, which is just about my favorite book.

Tim: I remember reading, or someone telling me, that a lot of the brilliance of Gatsby was in Maxwell Perkins' editing, who brilliantly pared the book down to the slim and perfect map of imagery and symbolism that we all know so well.

Andrew: That's new to me! What do you think I'm going to do if that's true?

Tim: Haha, well, I don't even remember where I read or heard that. But speaking of Gatsby—of course I'm sure you know that Dancer from the Dance is often called "the gay Gatsby." Did you pattern Malone, your romantic and mysterious protagonist, on Jay Gatsby?

Andrew: Yes, but not consciously. When Dancer was submitted to publishing houses, a Knopf editor turned it down by saying it was too much like Gatsby. I mean, what's wrong with that? [laughs]

Tim: I think one of the parallels I've heard is the shirts. Gatsby throwing all his gorgeous tailored shirts in the air, and Malone's massive collection of perfectly faded sexy 1970s clone flannel shirts and T-shirts in every color. Was that conscious?

Andrew: Totally unconscious.

Tim: I know that often after having written something, I become aware of the passage in a book, film or even TV show I kind of cribbed it from. Is that you?

Andrew: I think so. But I also think that if you keep on writing, you become more self-conscious. The thing about writing is that you don't want to know too much about what you're doing. Like when playwrights say that at a certain point, their characters took over and they were no longer in control.

Tim: So how do you figure out your structure as you write, if you don't outline in advance? Does it evolve as you write?

Andrew: For some books more than others. This newest book was like being on a horse that was out of control. I kept thinking the pressure of having a deadline would make it clear to me. In the Marx Brothers movie Go West, they're on a train and keep going between the furnace and the passenger cars. That's what it felt like writing this book. I just kept thinking, "Keep going—it will reveal itself."

Tim: It's your first novel since Grief.

Andrew: Yes, 16 years. I was shocked.

Tim: Our mutual acquaintance William Johnson, who was at Lambda Literary for several years and is now at PEN [and interviewing Holleran in Ft. Lauderdale on July 23], calls you "the Sade of writers." You know the singer Sade? She only puts out an album about once a decade, if that, and is very avoidant of the spotlight. Can you explain this rhythm of yours?

Andrew: I'm so dependent on writing that I sometimes wonder how people get through life without doing it. It's a buffer between you and life that enables you to try to make some sense of it. But what happened to me was the digital revolution. I remember I was on the Stairmaster at the Y in D.C. one day in 2008 reading the print version of The New York Times and I read that my longtime book editor, Will Schwalbe, decided to leave print books to start a recipe website called Cookstr. So when I lost Will, I lost my connection to book publishing. I look back now and ask myself, "Why weren't you more aggressive and self-reliant? Why didn't you try to publish at another house?" I don't know the answer. I guess I'm just too passive. But I did keep writing, stuffing my computer with novellas and stories. For a while I published in a print magazine called Bloom. I didn't want to publish online. I was a real Luddite. So that explains the 16 years. My goal now is to try to get my unpublished stuff published.

Tim: Oh, wow—so you are sitting on a lot of unpublished stuff?

Andrew: Well, that sounds—uh—dramatic But yes, I am. Can I publish something I wrote between 2008 and 2010? Is it relevant?

Tim: I would very much want to read it, whatever it is, and I hope I will. Can I ask you—I had a critical juncture, I would say, in the late 2000s, when my fiction writing had stalled out and I really had to decide if I was going to take it up again, and finally decided I had to or I would spend the rest of my life miserable. Have you ever had a juncture like that?

Andrew: No, because I never even knew what else to do with myself. I can't even go to the post office without coming home and writing about a woman I saw and a gesture she made. That's what I mean when I say that I don't know how people get through life without writing. You'd think it would help everybody.

Tim: Across your books, you're often reading of a protagonist who appears to have such a profoundly empty, lonely life and I think it's hard to not ascribe that to the writer. But at a certain point I reminded myself, "Andrew is writing. He’s actually doing something meaningful that his characters are not." The writing is the buffer between the person and the emptiness. Does that make sense?

Andrew: It makes total sense. Recently, I opened up my story collection, In September, The Light Changes and read a story I'd forgotten called "The Sentimental Education." It really caught that loneliness and emptiness. The difference is that I was able to write about it. People always assume the narrator is the author, and you have to keep reminding people that, no, the person who wrote this is not the same.

Tim: When you're writing, are you conscious of leaning into things like abjectness and shame in a way that is dialed up from how you experience that in life?

Andrew: Yes. It was like when you're writing and you feel you've opened a vein and you go with it. Writing this new book, I suddenly realized I was able to write about old age and I just didn't care.

Tim: In all your books, you lean so hard into this isolation and loneliness, this void, that it's almost cleansing. The new book is such a hard, unflinching look at getting old and nearing the end that I felt like I almost came out the other side and got past the fear of it. Are you conscious of that, writing it to the point of catharsis?

Andrew: No, and you're really making me have to think about this after we hang up. I didn't know I was doing that and now I have to ask myself why.

Tim: Why do you think?

Andrew: Off the top of my head, if a writer does that, they must be really unhappy and they’re venting. What's the difference between venting and catharsis? Catharsis is good—venting is just unloading.

Tim: But one has to vent, right?

Andrew: James Merrill, the poet, wrote a memoir called A Different Person, about his homosexuality and coming-out. And his mother was horrified. "Why do you think anyone has to know about this?" she asked him. And he said, "It's not that anyone has to know—it's that I have to tell.”

Tim: Hm. I sense in your narrators this real tension between well-bred politeness and—this almost perverse, I'm-not-going-to-let-you-look-away from some really ugly stuff.

Andrew: Yes, that's totally astute. I'm totally polite but I'm going to scream.

Tim: It's kind of rage in a way, right?

Andrew: Yes it is.

Tim: What feelings come up for you when you're writing a scene that you know is hard to read?

Andrew: When you're writing, you're so engaged, if you're lucky, that something is working, drawing the language out—I don't think about it. I grab it and go with it. When I taught, I'd say to the students, "Look at your story and ask yourself where the language is most interesting and most fluent. That's where you're finally writing about what you should, and you need to cut back all the dead stuff." Is the language alive and interesting? If it is, keep going—you've hit the spot. To go back to your point, I don't think about structure. It's in the moment.

Tim: But on some instinctual level, you must be aware of beats. Because the stories swing between periods of time. You have to be thinking about whether you're going to end the book in the present or the past.

Andrew: I wish I could say yes, but— [sighs] Did I know how this latest book was going to end? I didn't, really, and I had doubts about that last chapter, which is so downbeat, I thought, you can't end it like this. But I kept it because I loved the writing.

Tim: Yes. Well—you're such a lush writer. Your powers of description are insane. And this extreme lushness to Dancer from the Dance and Nights in Aruba.

And I sense that come AIDS, basically, your writing got starker and blunter and not as wildly lyrical. Not less powerful, just starker. Has anyone else ever noted that?

Andrew: No! And I think it's because of old age. I'm getting less patient and romantic. I think that's what it is. Which is a good thing! There are good things about old age. You have no time for the bullshit.

Tim: Right. As I was reading The Beauty of Men, I had the impression that the protagonist, Lark, is really old.

But in fact I realized he was about 50—about my age. Did you feel that—

Andrew: Prematurely old at the time? You can be prematurely old in your way of thinking. Anxious, pessimistic—but early on in life. You have a dark view of things. That's about temperament.

Tim: Dancer, well before AIDS, still has this incredible shroud—

Andrew: —of doom and hopelessness.

Tim: Yes. I was very much like that in my twenties. Was that you too?

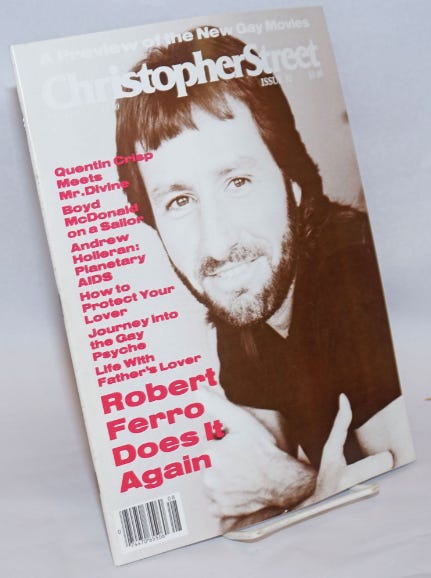

Andrew: When I was writing for [the defunct gay magazine] Christopher Street after Dancer came out, someone wrote me a letter saying, "You have what the Jesuits call 'morose delectation.'" And I think that means taking pleasure in morose subjects and gloom and doom. And I wrote back, "I think you're right." I've always felt a little guilty about that, because it skews life in a way that probably isn't healthy. But whatever makes you write is what you're stuck with.

Tim: You mention that anecdote a few times in your writing, and I thought, "Well, that letter-writer nailed it." Because you go so deep into sadness that it's almost beautiful and sensual. Kind of a wallowing. Kind of when you keep scratching an itch harder and harder and you know that at some point you'll bleed, but it feels so good. Is that what it's like for you?

Andrew: I think so. And the only antidote that enables that is to have humor at the same time. Nights in Aruba, there wasn't that much humor in there. I'm always trying to balance the two. But yes, there is a pleasure in going into the sadness. I mean, do you think this is Irish Catholic—?

Tim: I was raised Catholic, too. I was going to ask, do you think it's Catholicism? Let's face it—it's a very sad and sensual story.

Andrew: To say the least! But my sister has none of that, while I was gobsmacked by Catholicism.

Tim: Do you still go to church?

Andrew: No. But later in Kingdom of Sand, the protagonist is so lonely that he thinks of going back to church. There's a scene where he sees the Mexicans in his town in Florida having a Day of the Dead procession and wonders how long their faith is going to last in the U.S., which is so rational and scientific. That's not distant from what I've thought: is it time to go back to church?

Tim: Where did the title Kingdom of Sand come from?

Andrew: It was title block. Because titles usually are the most fun. But I wanted to call this book Florida. But the writer Lauren Groff took that. I had different options, but Kingdom of Sand seemed the least disagreeable. I wanted to call it The Cockroach Cemetery, but the publisher wouldn't go with that.

Tim: Cockroaches do play a really unforgettable role in the book, indeed.

Andrew: Because it's about death. But nobody would take that title seriously. The Kingdom of Sand is a very 1950s Taylor Caldwell middlebrow fiction kind of title.

Tim: But it has to have some connection to the book for you.

Andrew: The whole peninsula of Florida is made of sand. There's the connotations of time passing and of instability, and I like all of that.

Tim: Yes. So one thing I wanted to ask—as early as Dancer, there is this real tension in your books between the sensual and intellectual pleasures of city life and the beauty of the natural, rural world. And in terms of why you left New York relatively young, in your early forties, and never fully came back, my hunch is that—in addition to leaving to care for your mother—if you had to choose, you would pick natural beauty, literally the sky and the forest and that kind of thing, over city life. Correct?

Andrew: I can't live without either. When I'm in Florida and taking my walk, looking at egrets and bunnies and wild turkeys, I think, "You are the luckiest man on earth—be grateful." But after a while, I'll think, "My God, how can people live in a town like this and not leave?" And I'll have to go back to the city, NYC or D.C.

Tim: Well—here is a blunt question. I was reading the new book alongside William [Johnson], and said to him, "My God, I hope Andrew is not as lonely and isolated as this character." And William said, "In fact, he has a lot of friends he's always in touch with and spends half his time in D.C. The isolation in the book is dialed up." True? Because I hope so.

Andrew: William is totally correct and very astute. But there are literally many days where I go without any human contact. I'll actually linger in the yard because I know the postman is coming. The pandemic was difficult. I was literally stuck here.

Tim: And is that town Jasper, as you call it in the book? Which I looked up to realize is in fact a real town in northern Florida.

Andrew: I'm not going to say. I don't want the people in town reading this book. But when I realized I couldn't go back to D.C., then I realized how socially isolated I really am here. I started getting paranoid and pessimistic. That's lifted a little.

Tim: Do you think you're simply someone without a lot of need for human contact?

Andrew: To put it a more positive way, I'd say I'm someone who doesn't mind being alone. Where it says in my author bio, "He lives in Florida," it really should say, "He lives in his head." We're writers—we take a great deal of pleasure in reading. Wouldn't you hate to have to need people constantly as a distraction?

Tim: I've definitely gotten better at keeping my own company as I've gotten older, and I'm happy about that. Do you still have a lot of friends in New York?

Andrew: As you get older, many people finally leave New York for other cities or their hometowns. Your friendship network becomes answering emails, and that's sad. That's not good.

Tim: In The Beauty of Men, there is an unbearably sad and bitter sense of the protagonist's premature sense of getting old having a great deal to do with having lost so many NYC friends to AIDS—a tremendous sense of early loss. Was that experience true for you?

Andrew: In a sense, leaving NYC in 1983 spared me the experience of watching so many friends waste away and die. I heard about it through the phone, which gave me a distance.

Tim: And you never fully went back to NYC, even though you kept an apartment here for many years.

Andrew: I didn't have the option. My mother had fallen and I was taking care of her until she passed in 1991.

Tim: And so much of The Beauty of Men, from 1996, is taken from your experience of caring so intimately for your mother, visiting her daily and attending to her grooming even once she was in a nursing home. I loved that you depicted that in such, really, agonizing detail—your intense love for each other and your terror at the prospect of her dying and the huge hole she left in your life once she did. As gay men, we don't generally have children and I feel like we don't talk enough about the passage of our parents—especially our mothers, with whom we often have extremely close and complicated relationships.

Andrew: The thing about gay life that is so hard—I'm more and more coming to this idea—is finding a way to express love. Because it's natural to love your children, and we [often] don't have that. So whom are we going to love? How are we going to love? We're very good on sexual desire—we know that and we act on it—but how do you find a way to express love?

Tim: Your avatars in your books are usually single, or they have very short affairs that burn out. May I ask if you now have, or have ever had, a longterm relationship?

Andrew: I had relationships that you would not consider relationships. Four months to me was an achievement. I would be very attracted to the person and grateful for them, and it was mutual, and we would try to be boyfriends, but not long into it, it would disintegrate on my part. I would think, "What am I doing with this person?" I was never relationship material. And yet now I envy people who did have relationships and were or are together over a long period of time. I once said to my sister, "You're married—you can relax." And she said, "You don't get married to relax." She said that it never stops presenting annoyances and frustrations.

Tim: You wrote rather famously in Dancer from the Dance that, at the end of the day, the people we are closest with are the friends that we go out dancing with. It's a beautiful passage about the intensity and importance of gay friendships, especially in the absence of romantic relationships, or how short-lived they can be. Do you think that as gay men we can give to our friends love as fully as one does to family members or partners?

Andrew: But what if we admitted that? Would it put too much pressure on the friendship? Because the essence of friendship is that it's not anything more than friendship.

Tim: Do you feel like you have that intense friendship with some people, like a real do-or-die friendship?

Andrew: I don't, which I think has to do with having lived in two places [Florida and/or New York or D.C.]. You really have to live in one place to achieve what you just mentioned. I think I have a little bit of that but not much.

Tim: Your avatars in your books are all intense exercisers and very meticulous about what they eat and staying fit. Is that you?

Andrew: I couldn't exist without exercise. I'm a gym rat. I was just back in D.C. and amazed at how happy I was to be able to go back to the Y and see friends there. I was overjoyed. I thought to myself, "Is this what your happiness consists of?"

Tim: I have that feeling at the gym often too. I've been going to the same gym for about 20 years. When were you last in New York?

Andrew: Not in quite a while. Have you gone to that strange little island they built in the Hudson River?

Tim: Oh, you mean Little Island off 14th St. in the river, which Barry Diller basically paid for? Yes, I did go once—I was out running and I quickly ran through it.

Andrew: Do you think that gay life in New York is more invisible than it used to be?

Tim: Well—the current gayborhood is Hell's Kitchen. There are at least two gay worlds in New York right now. Hell's Kitchen is the clone world—the basic gays. Then there's this whole queer nonbinary, much more people of color, genderfluid, painted fingernails, which is more out here in Brooklyn, like Bushwick. Can I ask you? How would you taxonomize the different gay types in New York in the 70s?

Andrew: Let me ask you first: How big is the nonbinary segment?

Tim: Hm, that's a good question. Everything has collapsed into itself. In a prior day, there was this gay man versus lesbian binary, and all the jokes about gay men versus lesbians. Now with this nonbinary genderqueer—

Andrew: Is there a hostility between the basic gays and the nonbinaries?

Tim: I think both a hostility and an attraction and curiosity. Andrew, you're too good at turning the interview around on me!

Andrew: But this is so interesting to me, because I've seen this tension starting and I'm thinking, "Who would have ever predicted this?"

Tim: The only thing I can compare it to is, say, squares versus hippies circa 1968. There's a real feeling I think among us older gays that if we want to not be totally irrelevant, we have to make an effort to understand this aesthetic that is not very exciting to many of us often. You can go to a party out here in Bushwick—very young hipster, much more racially diverse than the downtown Manhattan gay scene was before—and there are still beautiful gym bodies. I don't think the desire for attributes that scan as masculine has disappeared. It's just in the mix with this other stuff. So this is a typical guy in my neighborhood: A 30-year-old guy with a very nice muscled body who will wear fishnets and a bustier and platform boots to go out dancing.

Andrew: I'm just on the floor! One more question! So, what is the look for the basic gays now?

Tim: They are what would have been called the clones in the 70s. Like, very shaven head, military-type buzz cut, very gym body, and very proudly slutty, sashaying down Hell's Kitchen wearing tiny shorts, a crop top, white sneakers and socks, a bit of a retro 80s-90s porn look. And then maybe your nails are painted black or you wear a string of pearls or some glitter on your eyes. That is the 30-year-old clone of this moment. So were there any gay types beside the beard/flannel shirt/501s/work boots clone of the 1970s?

Andrew: No! It was a uniform. But are there still unobtrusive gays in NYC? Normal-core or whatever it's called who just go to work and—

Tim: Of course.

Andrew: So the gays you just described are the ones who are really acting out and telegraphing gayness.

Tim: And often they're in Hell's Kitchen. It's the ghetto. They're preening for each other.

Andrew: So, in my day, I lived in the East Village, on St. Mark's Place, and I was always a little proud that I wasn't a West Village clone. A little superiority on my part for being a bohemian artist. But were there people who were really femme or nonbinary? Very few. [The artist] John Eric Broaddus, people like that. But the clones dominated. They were the rebellion against the [effete] 50s gay, and the whole point was reclaiming masculinity, going to the gym and getting muscles. They ruled the roost.

Tim: But what about the Warhol crowd in the early seventies when Dancer from the Dance starts? They had lots of transsexual types.

Andrew: Good point. And yes, they were on my radar. Caffe Cino—that was the Warhol crowd before The Factory. I think I and my friends looked down on them as being rather mean and exploitative. Warhol scared me. I thought he was a mean queen who was draining people and using them. I heard once that Warhol passed the spot where a queen on acid had jumped to his death and Warhol apparently said, "I wish I'd known he was going to jump so I could have filmed it." That may have been an affectation on his part, but I thought they were just too mean. Tough girls. But for the most part, there was an Upper East Side fashion and art gay crowd, there was the Factory crowd, there was the East Village crowd, the West Village crowd, then soon enough the Chelsea crowd. But overall masculinity was always the factor. But has the nonbinary thing really changed that or not?

Tim: I think it has and it hasn't. I don't think I'd even heard the word "transgender" in 1991 and when it was explained to me, I was like, "Oh, so those are people who want to be a drag queen all the time—okay, cool, whatever." I didn't really understand it as this deep "I was born this way," born in the wrong body, this deeply suppressed, marginalized community that was going to rise up politically the way they have—the way gays did in the 1970s.

Andrew: So you then believe in it—that these people are genuine and their body dysmorphia is a real source of unhappiness?

Tim: Well—I'm comfortable in my cisgender gay male body. So I'll never purport to know what other people think or feel. I think maybe there's a continuum between "I'm a woman or man inside and I'm literally dying until my outside matches my inside." And then, especially now with young people—say you're a girl but maybe you don't want to be the traditional idea of a girl, so you say you're nonbinary and you don't have to be, quote, a girl the way it's defined by society. I think maybe it's a spectrum. I certainly know people roughly my age who have declared themselves nonbinary in recent years and use "they/them," and I'm like, "Okay—you're my friend. Why wouldn't I honor that?" I don't fully get it. I mean, they basically look the same, versus someone where you can see the transition happening and they are opening themselves up to ostracism wherever they go. What do you think?

Andrew: Well, I ask because there's a backlash now. I thought the gay liberation movement was settled, with everyone married and living in the 'burbs and adopting kids, and then you realize it's not settled and the trans thing is reviving it.

Tim: Yeah, almost kind of like the Anita Bryant moment with gay rights in the 1970s—uh-oh, those people are getting too visible and demanding too much, and we have to fight back. These anti-trans laws are disgusting to me. Just like we as gays were their political pawns once, they're now using trans people in the same way.

Andrew: But I think some of the backlash is because this opening up of trans and nonbinary gives people options they don't want to have. We have to stop now! We've been talking for two hours!

Tim: But wait. I have to ask you about Puerto Ricans in your books. Because they're such a trope, you’re constantly mentioning them, yet there’s never an actual Puerto Rican character. I'm curious— look, I moved to New York from Massachusetts, a very white place, and I was besotted in the same way by Latins when I moved here. But looking back on the early books, how do you feel about your placement of them in the milieu?

Andrew: [laughs] You're such a —! Puerto Ricans were everywhere in the East Village and every time I went to Stuyvesant Square to cruise at night, I was very likely to go home with a Puerto Rican. I was attracted to them. It sounds awful, as if I'm categorizing, but I guess I am.

Tim: Well, desire is desire. You can't really help it.

Andrew: Exactly. And they were very attractive to me. So that was a huge plus of living in the East Village. So you're question was—am I sexually objectifying them in my books?

Tim: It's more about looking at it through the lens of forty-five years ago. Listen, I have things in my first novels—I used the N-word in my first novel—

Andrew: Did you really?

Tim: Yeah. It was the Black character using it.

Andrew: Oh, absolutely! I am so against this language policing. I cannot believe it. I think we've become so prudish and awful about it all. The sensitivity is over the top right now.

Tim: Well, it seems a little bit like the romanticization of Puerto Ricans in your books—do you feel like you subdued that over time, as society tells us as white men of a certain age that we have to look at our privilege? I'm very interested in this because it's all anybody talks about anymore.

Andrew: You're asking about a huge issue. My feeling is, the whole idea of judging the past by the present is kind of stupid. That's how people thought. We know the sins and the crimes. I don't see the point in constantly shaming, because human history is supposedly a progressive movement toward better things—and the past is the past. I think what you're getting at is, someone has written an essay about the racism in Dancer from the Dance [Tim: I think it's this one by Lester Fabian Braithwaite that was in Out in 2018]. But to me, to try to change history is a false sense of superiority. Right now, people are going to look back on us for things we can't imagine.

Tim: So I know we have to wrap up, but I want to ask you just a few more things. So, I have this group of friends who are all various degrees younger than me, and about once a month we go out dancing. And when we do, I vacillate between feeling invisible and out of place because everyone is younger than I am. But I also have moments where I don't care because it feels so good. Like in The Beauty of Men, when you talk about how gay men continue to go to the baths even when they're older and less desired just because it feels good to be around other gay men. I definitely have those moments where I'm just so happy to be dancing with other gays. Do you ever—uh, if not dancing, but where you are able to access that raw feeling of youth, of being so in the moment or the scene?

Andrew: The only time I feel that is at the gym. I don't go dancing anymore and I don't go into gay bars, even in D.C. And that's my own problem. I'm editing myself out because of age. Which is wrong. A friend once said to me, "We want older men in the bars." But I don't want to be subject to humiliation. It's the wrong attitude, but it's what I feel. So where do I feel gay solidarity? What we're doing now, I guess. But I don't go to a place anymore. And I console myself by saying the Internet has replaced that. But here you are telling me that people still go dancing. I would love to be able to go to the baths. I was in D.C. recently and almost did, but I just didn't have the nerve to do it. It's sad, because you're putting yourself on the shelf, and you should just get over it.

Tim: It's kind of getting past one's ego. And I don't mean that in the superficial sense of getting past one's wounded vanity. But getting past one's sense of self and just being in the connectedness of the experience. Which can be hard.

Andrew: So, the younger friends you go dancing with—they're not embarrassed by your presence, are they?

Tim: [laughs] I don't know—you'd have to ask them!

Andrew: They probably wouldn't go with you if they were.

Tim: Sometimes I want to say to them in those moments, "God I feel so old and invisible." Going back to your books, there's something very charged about admitting one's own humiliation.

Andrew: I wouldn't tell them if I were you. They'd just want to reassure you.

TIm: So I want to end how I always end, by asking a two-sided question. The first part is, what's your biggest regret in life?

Andrew: I did not live enough.

Tim: How do you define "live"? I mean, I often say to myself, I am so grateful that the thing I wanted and needed to do, I've done, which is to be a working writer. And writing is living. Do you derive a sense of accomplishment from that?

Andrew: Yes, I do. I regret not having lived more—this is sick—because I would have had more material to write about.

Tim: That's not sick for a writer to say. [laughs]

Andrew: But it is sick in the larger sense. One shouldn't put writing over life.

Tim: So what do you mean—having more sex? Traveling more?

Andrew: As for travel, I became afraid to fly at one point. But really, travel is just sightseeing. So was it having a relationship? But I wasn't fit for that. So what would it have been? I spent 20 years in Washington teaching in an MFA program—a very pleasant, easy life. I ask myself now, how could you have wasted those 20 years doing that? But then I ask, well, what would you have done with those 20 years?

Tim: So can you put your finger on one thing you wish you'd done more of?

Andrew: [throat clearing] I would probably say— [ long pause] been more social.

Tim: Spent more time with friends?

Andrew: I wish I had known more people. And yet I treasure the people I did know tremendously, to the point where I'm still writing about them. Is it cheap vanity to say I wish I'd known more interesting and famous people? Should I have known the Warhol crowd, so I could've written about them in old age?

Tim: Okay. So the flip side is, what are you most proud of?

Andrew: Oh, what you said—writing. But also having been there for my mother. But really it’s writing. Writers are fiends. We're such strange creatures. So obsessive.

Tim: Ok. So this is the final question. You have a really beautiful body of work to be proud of. And among it is one book, Dancer, that has attained a Gatsby-like status that defined an era. Does that bring a feeling of peace, that you created something that truly will outlast you, which even most published writers can not say?

Andrew: I'm very grateful for it. Every writer wants that. So, sure. On the other hand, you're terrified of being a one-hit wonder where nothing else you write matters. John Knowles, who wrote A Separate Peace—he wrote so many books after that. But isn't it awful he'll always be known for A Separate Peace? So Dancer is something I've always been trying to run away from and surpass. But as you probably know, it's so out of our control. You can't design the reception a book will have.

Tim: Well, I'll close by saying that—

Andrew: Oh, I wasn't fishing for compliments.

Tim: No, this is a specific observation, which is that everything you wrote after Dancer follows from it in a way that feels of a piece and that you can read almost as sequelae to it. Whereas other people have a hit, then all these other books that don't relate to it in some way. But Dancer is the perfect portal to your other books, because it's all kind of dialed-up memoir, right?

Andrew: It really is. Should I have been writing memoir instead of novels all along? Writing creates so many unanswered questions. If you were a brain surgeon, you'd get better at it over time, but in writing, it doesn't work that way. You end up in the same state of ignorance that you started out in.

Thank you for supporting The Caftan Chronicles! I’ll see you in July!