The Many Realities of Choreographer David Rousseve

The Guggenheim Fellow dancer and self-proclaimed #zaddy gets real about everything from sexual abuse and fetishism to being a "whore" Down Under and how the 1980s NYC dance world set him free.

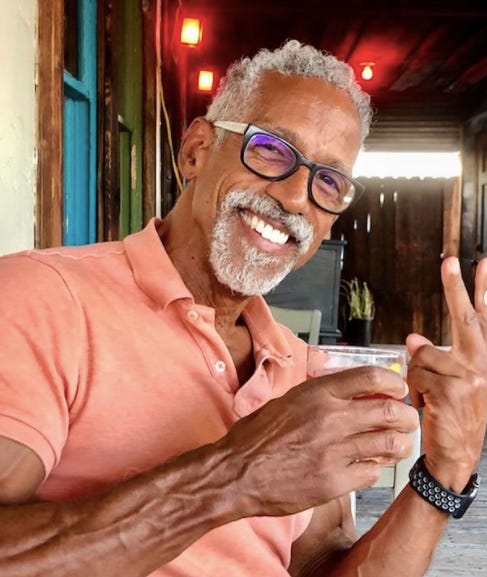

Okay, I'll admit it. As much as I love dance (I really do), I'm not a hardcore dance wonk (the way I am, say, a hardcore theater or literary fiction wonk), and the reason I wanted to interview longtime dancer and choreographer and Guggenheim Fellow David Rousseve was because, after we somehow became Facebook friends, I just couldn't get over what a sexy older gent he was. Fine, sue me—I had a crush! Still, I'd been familiar for years with his name from seeing it on Chelsea performance marquees like the Joyce and Danspace, so I figured that if I reached out and David accepted—which, happily, he did—I could do a deep dive into his work before we talked.

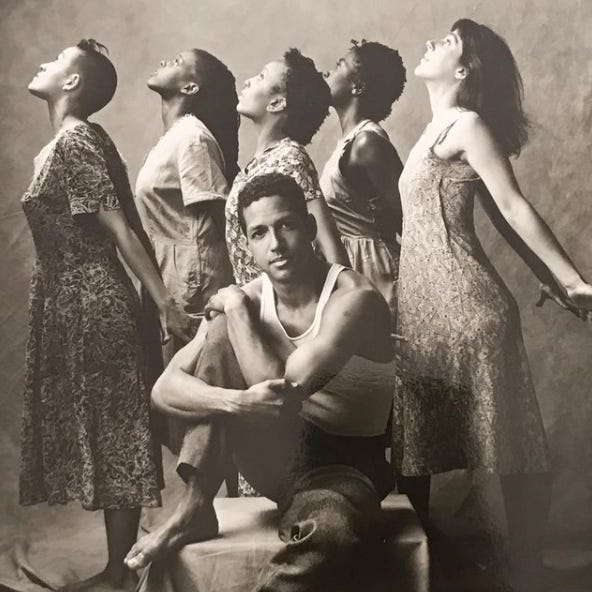

And I did just that, watching three of David's evening length pieces of the past decade-plus: "Halfway to Dawn," his right-before-COVID meditation on the great gay Black composer Billy Strayhorn; 2014's "Stardust," centering around a lonely gay Black boy who we never meet but only hear his voice via screen transcriptions of his texts (the piece in many ways seems to prefigure the 2016 Oscar-winning film "Moonlight"); and 2009's "Saudade," named for a Portuguese word meaning "bittersweet yearning" and, toward its end, containing a monologue that is deeply revelatory about Rousseve's own life (more on that later).

David's pieces are incredibly beautiful, merging performance art, theater, spoken word, video, the written word (via projections) and modern and postmodern dance vocabulary. David, who is 62, has a theater background himself since early childhood, and that comes through in the panoply of character monologues he undertakes in his word, almost Anna Deavere Smith-style and almost always channeling Black Americans of different eras and ages. So I definitely want to urge you to see a Rousseve piece the next time you have a chance; you can follow him at his website or via his delightful, thirst-trap-filled Instagram.

But the funny thing is, in the two hours that David had to give me on the last day of September, we actually never really got around to deeply discussing his dance work because we ended up going so deep into so many other aspects of his life. Which, honestly, is fine with me in a sense, because I'd always wanted these Caftan Chronicles interviews to become anything they wanted to be, based on where the conversation was going. In a way, that's what makes them special for me compared to paid interviews for media outlets, where you must discuss the upcoming work the piece is pegged to, even if, honestly, you are more interested in other aspects of the person. For me, that wasn't the case with David—I'm a longtime Strayhorn fan and could've probably spent at least an hour with him discussing his gorgeous, multilayered Strayhorn piece alone. But it just didn't go that way. Hour Three would've probably been about David's dance work—and maybe we'll do that conversation someday.

But again—I don't regret what we did rather than did not discuss. Because we had an amazing conversation. Even before talking, I sensed from watching online interviews with him—and from his Instagram!—that he had an especially open-hearted, open-minded spirit. And I wasn't wrong. He's a sweetheart, but he's a reflective and brainy one, so...well, rather than my going on longer, why don't you just dive into our talk? Here we go...

Tim: David, thank you so much for agreeing to this conversation. So let me start in a place I often like to start, which is asking you exactly what you've done so far today. You live in a cute little house in West Hollywood, yes? That's what I sense from Instagram. [David moved to L.A. in 1996 to become part of the World Arts and Culture/Dance faculty at UCLA, and he's been there ever since.]

David: Yes, my partner Steven [Rubenstein, a high school teacher] and I have a little 1912 Craftsman house. I moved here about a year before we met [in August 2019] and then Steve moved in with me. It's actually a front house and a guest house in the back that we use as our bedroom. That worked out really well during the pandemic because Steve taught on Zoom from the back house and I taught from the front house.

But today, I got up around 6am, which is around when I get up every day because I'm an insomniac and also because Steve gets up to get ready for school. So we read the paper and have breakfast together—today, oatmeal and boiled eggs, and a green drink, which we have every morning. Luckily, Steven loves to cook. He made this really beautiful quiche which we had every other day this week. But today for lunch I had some leftover pasta puttanesca from two days ago. I'm pescatarian, so we have fish almost every night. I cook twice a week. My abilities are less than his, but I can make some Creole dishes from my childhood [he grew up in Houston; his father was from New Orleans] like shrimp étouffée or gumbo. We do a lot of grilled fish and pasta. Steve surprises me constantly. He's constantly trying new things from the New York Times cooking section.

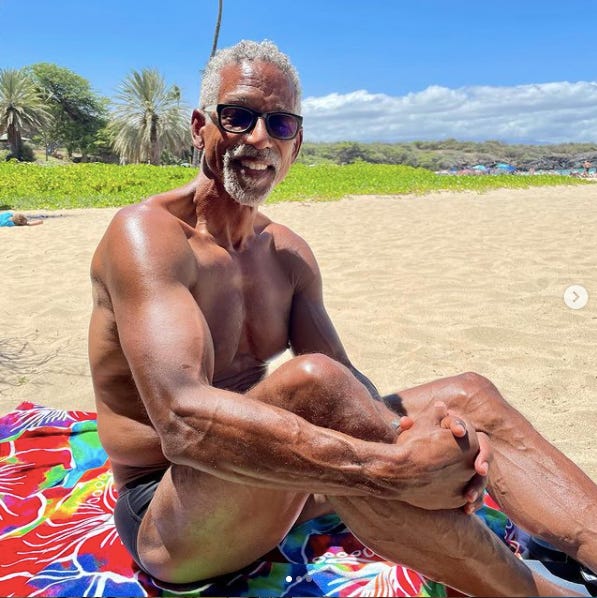

Tim: So I may as well just come out and ask you how you stay so lean, especially eating a lot of pasta—because your body is insane. You are in amazing shape.

David: Haha, thanks. I try to do something physical every day. So after breakfast today, I worked in my home office a little on some UCLA stuff, then I went to the gym.

Tim: You go to the WeHo Equinox, yes? I know that from Instagram.

David: [laughs] Yes, I do. So today I did the elliptical for an hour, but usually I only do it for 10 minutes, then Pilates, then weights—a major and minor muscle every time. But now I'm really worried because—and here's the age thing—you can't do what you do when you're younger. I started doing really heavy squats after my double hip replacement. The doctor had said to me, "You can't do anything now but swimming and the elliptical." I thought, "Well, that's not going to work" [and he proceeded to do heavy weight training]. But now my hip is hurting, so I'm like, oh fuck...

Tim: Wait—how heavy are your squat weights?

David: Pretty heavy. I put six 45-pound weights on the bar, three on each side.

Tim: What!? That's insane! The most I've ever done is four, two on each side.

David: I know, what was I thinking? There's a constant gentle pain there and I know my doctor's gonna be shady [when I tell him]. The hip replacement was about nine years ago. I think I felt like I was young to be getting a hip replacement, because they used to not do them before your seventies, but I had osteoarthritis, probably from abuse from dancing. But the rehab from the surgery went so well that, for better or worse, I didn't attach it to age. But as time went on, I was like, "Wow, this is getting older." You feel like, "Wow, this body is degrading rather quickly."

Tim: But are you aware that you look amazing?

David: That's very sweet—thank you. I think I'm doing the best with what I've got. I was in a relationship for 26 years with another dancer, Conor McTeague. We broke up in 2018 but we stayed close as a queer family. But once I was single, I was like, "What are these [gay hookup] apps?" But then I met Steve exactly two years ago in 2019.

Tim: So you were single for exactly one year. What was that like?

David: Well, I would say that in some ways, it was great. Conor and I were in couples therapy for ten years—it was finally time to call it a day. But a year before we separated, we decided to have an open relationship. But that would not have been my choice. I mean, I would never be in a longterm celibate relationship. Part of why we were in therapy was that we'd stopped having sex. And we'd opened things up, but that was awful. I didn't like it at all because there was no communication about it.

Tim: It sounds like you were more sad about the relationship dying than you were excited to convert it to an open relationship.

David: Yes, it was sad—a dying relationship, and I knew that opening it up was just a step toward separating. So once we separated, I was happy to be single and finally on my own, and to be able to have hookups and not feel guilty. So in terms of how I feel about how I looked, that is where— people started coming out of the woodwork! I didn't know that there was such a daddy thing going on. Which is not really my thing. I'm not attracted to really young people. This is why I went primarily on Scruff [versus Grindr], because when I lived in New York in the 1980s [from 1981 to 1996], I didn't like going to the West Village at all, because it had a very exclusive Ken-doll white aesthetic. I hated WeHo in L.A. for the same reason.

Tim: Have you had a "type" over the course of your life?

David: No. Recently, I learned on Grindr a really great word: sapiosexual [meaning to be attracted to intelligence]. I'm not looking for gym boys but I do like people who are in their bodies, aware of their bodies. But I'm more interested in connecting intellectually and philosophically.

Tim: But I must say that you do not hesitate to hashtag yourself #zaddy and #silverdaddy in your many shirtless Instagram pics.

David: [laughs] I started doing that on tour with my last piece. We got such good laughs. I had just joined Instagram. Here comes my not only narcissistic but small-minded moment: I was talking to this really hot guy who had all those hashtags under his pics—and oh my God, he's got like 800 likes. And so I literally copied and pasted his whole list, hoping I'd get more likes if I used it. And I did. So I guess when you ask me how I look, I notice right off the bat that on Grindr, Scruff and Instagram, when you post a thirst photo or two, it goes through the roof. So I thought, "I'm gonna play it up."

Tim: Do you think that was about rediscovering your, like, sexual mojo after ending your long-term relationship?

David: Yeah. But bottom line, we all have to know ourselves. So while it was great to be able to have as much sex as I wanted—and my therapist kept saying, "Go out and try everything you want"—I also knew that that I was a relationship person. And there were very few relationship people out there. And I'm not really attracted to the 25-to-40 guys who are looking for a daddy. I don't find them that interesting in bed, to be honest. And out of bed? What do we talk about? I don't want to mentor you.

There were a couple of people my age I was interested in. And to one of them, I said, "Wait, your last boyfriend was 19?" And he said, "Oh, absolutely I'm interested in people my own age—but they don't take care of themselves physically." And that was a red flag for me, because I'm not gonna look the way I do forever. So I thought, "This date's over."

Tim: Why do you think you are a relationship person? What does that mean to you?

David: I really enjoy sharing the world with another human, whether that's a good meal or traveling or going to a museum. Yes, I can do all those things by myself. In fact, for my sixtieth birthday, when I was still single, I jumped on a plane and went to Australia by myself. I don't enjoy traveling by myself as much with another person. I don't like being alone. But I'm laughing because, with Australia, I thought, "Well, you know, I bet I'm gonna get there and be objectified, like, Oh my God, here comes the Black man." And I thought, "Bring it on, Aussies—I'll be your little fetish. I'm gonna be the whore of Babylon in Australia!" And then I get there and there are gorgeous men. I've never been that uncomfortable in my entire life around the lack of diversity of Sydney and Melbourne.

Tim: Had you ever been somewhere where you'd not seen yourself reflected around you?

David: No—not to that extreme. And no one was particularly racist or odd, but I did get a lot of attention. And the moral of the story is—I'd been like, "This is nothing but a ho trip for me." And then the day after I got there, I got an email from a lovely, beautiful person I'd slept with a a week before leaving, telling me that he'd tested positive for some STI—I can't even remember which one—and he was worried about giving it to me. Oh fuck, you gotta be kidding me! Here I am on my whore trip! Ethically, can I sleep with people? No, that's so fucked up. So there I was in Sydney with no sex. So I got tested in Sydney and did not find out I was negative until a week later when I was in Melbourne, so I thought, "Okay, back to whoredom." And then I found someone and we had a mini-affair and I ended up sleeping with only him.

Tim: So even on your whore trip, you ended up in a sort of relationship.

David: I like to go deep. I think my choreography, for better or worse, tries to go deep—and I'm interested in a deeper engagement in relationships, which is not what everyone wants.

Tim: So what was it about Steve that worked for you?

David: [first he tells a long story about how they met, at an event where both of them thought they were on a date with the same third guy, who'd double-booked]. I was immediately taken with him. He came up to me in a very alpha way. I thought he was really beautiful but also sensual and super-smart. He has his PhD in English lit and knows so much about drama and theater and loves avant-garde dance. He can keep up with me, and then some. And we moved in together not long after that—we met in August and moved in around February. Then COVID hit. Thank God we had about six months to get to know each other. I have to say that COVID was positive for us—it felt like packing six years of existing together into one or two.

Tim: What is new about Steven for you that you have not had prior?

David: That's an easy one. Not everyone needs to be in therapy, but I appreciate people who are, or have been—or are in a 12-step program or spiritual practice, or some way to self-reflect and meditate, or write. And he's a real self-reflector, so the conversations and level of intimacy is at a new high for me. He was actually married for 32 years to a woman—and we got divorced at exactly the same time.

Tim: Was it weird to have so much more experience in gay sex than he did?

David: He wasn't having gay sex during his marriage, so it was very new for him. But I'd say he's incredibly sensual and adventurous. By the time I met him, he was pretty fluent!

Tim: So I wanted to ask you, you mentioned earlier your fears of being fetishized in Australia as a Black man. Has being fetishized been a big issue in your life?

David: It has been a big thing, yes. It was even more prominent for me in places like Germany, where they don't have a lot of people of color and hence fetishize them, but I experienced it in New York, too. I was an East Village guy because the gay community there was more diverse.

I feel two ways about being someone's fetish. For the most part, it's kind of demeaning. You're only seeing me in my Blackness, and not even in my true authentic Blackness, but your own version of what Blackness is. Maybe it's okay for a one-night hookup, like when I was in Australia, but it's still someone wanting you to be something that they've assumed you are. It's one thing if you have a partner and you role-play and participate in each other's fetishes. But it's another if that's all you can be [to someone].

Tim: I wanted to ask you —you have a very open vibe. Is this something you know about yourself?

David: The main thing about me is, I am relentlessly curious. I wanna find out more about everything—artmaking, life, the meaning of life. How does this gadget work in the kitchen? [laughs] It's probably why I became an artist. So, going back to dating and age, I wasn't throwing shade at people who are into very young people. It's just that young people don't have enough life experience, so it's rough for them to know how to keep my attention.

I'll say this about being open. My first trip to Europe, a few years after I graduated from Princeton in 1981, was with my mother, who was a child of the projects in Houston. [She died in 2019].

People used to say to me, "I'm the first in my family to go to college," and I would think that my mother was the first in her family to go to elementary school. She grew up in abject poverty. So, on this trip, I recognized something. We were at a flea market in Italy, and my mother was known to be bold and outspoken as they come. If you're from the deep hardcore projects, you have to have a boldness in order to survive. So at this market, this guy was selling silk scarves, and she said, in English, "How much?" And he really scolded her. He said, "You have to try to speak Italian." And I could see she was a little frightened, because instead of saying "Fuck you," she said, "I understand," and asked how much it was in her broken Italian. And I recognized myself in her, the paradox. This woman from the projects who is so bold—here she is, touring the world without her husband because he refused to go. And she was frightened, because the guy [selling the scarves] had all the power. And I recognized myself—making all these bold choices in life but doing so while I'm frightened. And it creates a lot of anxiety, because you're doing these things, but you're terrified. To this day, I'm terrified, including being open and vulnerable.

Tim: Why do you think you were terrified—and still are?

David: I was sexually abused as a child, maybe when I was six, by a cousin. That will destroy anyone's world. But I think it goes back earlier than that. You can't be a greater have-not than my mom grew up. When she had us, the hospitals were segregated—and of course, no po-ass Black woman is going to have one of the best white doctors come deliver her baby. But she did. She went and found him. She was determined that she was going to have all the things that people said she couldn't have. She was a bit of a tiger mom. She was not allowed to be in theater as a child, so, like it or not, I was enrolled in theater at age five.

When I was born, I came out yellow—but Black babies always come out a little yellow. But the doctor thought I came out yellow because I had pneumonia. So I stayed there a few days in an incubator and then they said, "Oh, his color has returned—we actually don't think he has pneumonia." But I can almost remember what it was like to be alone in an incubator. So I think [being frightened] goes all the way back to that.

Tim: David, you just brought up so much—including the sexual abuse. Are you okay talking about that?

David: Yes.

Tim: What I'm really curious about is, not the details of what happened, but how you understand it today. How do you fit it into your life?

David: I started becoming more public about it when I did a piece in the 90s called "Urban Scenes/Creole Dreams," about my grandma—digging deeply into the horror and destruction of the soul that that type of abuse does to children.

It was the first time my work was at BAM [Brooklyn Academy of Music], work that jumped between my grandma's story and mine living in New York at the apex of the AIDS epidemic. No doubt the apex of this work was a rape scene. It was invested with so much emotional energy and trauma that it took a while for me to realize that it wasn't about my grandma's friend, as it presented in the piece, but about myself. That occurred to me when female audience members very rightfully said to me [during the post-show Q&A], "You know, it's disconcerting, a man writing a story about the rape of a woman, performed by women, but choreographed by a man who has all the power." It was this really graphic monologue about violence against a young girl. And I said, "Oh my gosh—it's actually my story projected onto someone." But the emotional undertones are mine.

Tim: Wow. How did they react to that? Empathetically or negatively?

David: With a lot of empathy. And when we toured the piece, some people would say "Tell your own story," but most felt like, "You know, it's great to see a man who is trying to embody and become one with the ethos of a woman."

Tim: Well, that really touches on a very contemporary conversation, which is, is it okay for people to tell other people's stories in art, especially when there is a power or privilege differential? What do you think?

David: It depends. With my grandmother's story, we didn't share gender, but we shared race. I remember a woman [defending me] saying, "For God's sake, it's his grandmother." I don't think there are easy answers. But I'd rather have a first-person voice.

Tim: It's interesting because I think in our generation, roughly Gen X or young Boomer, there's been this ethos that cultural cross-pollination, borrowing from one another, is a good and beautiful thing, but this younger generation is very touchy about anything that smacks of appropriation and believes we all should "stay in our lanes," so to speak.

David: I'm a little bit thrown with all these current issues with art-making. I have a short film called "Enough?" that has an image of [Black man] Walter Scott being shot in the back by a policeman [in 2015 in South Carolina]. It's about the damage to Black minds and hearts of constantly encountering images like this. It didn't occur to me to announce ahead to the class that the film contained] images of violence, and an African-American student wrote to me, "That's triggering, and I'd request that next time you let us know if there are going to be triggering images of violence against Black bodies in the pieces you show."

Well, I was shocked. Then I thought, "Well, you know, for better or worse, she's right."

Tim: Wow. Well, being white, I am not going to speak specifically to what she asked—but more generally, don't you want to say sometimes that part of engaging in art is being shocked and upset?

David: Oh, yeah. I mean, don't ever go to a Pina Bausch [dance] piece or read a Toni Morrison novel, because they're filled with graphic— I mean, Toni Morrison is the person who means the most to my artistic— because the grit and violence is equal parts to the joy and the spirit. Maybe it's my old-school mentality, but you can bombard me with the horrors of the Holocaust, slavery. Because something has to be graphic for my brain and heart to be appalled.

Tim: So given this somewhat generational difference in sensibilities, what kind of a teacher to young people do you try to be?

David: Up until three years ago, I was very frustrated with the younger generation, as someone who did not grow up empowered or being taught my own self-worth. On one hand, I'm happy that young people seem to be empowered and know their self-worth, but I thought it was taken to an extreme. It's so "about you" that it's hard to reach in a new direction without feeling like you're not being listened to. So, I don't know what happened, but about three years ago—maybe the shift was in me. I love teaching the undergrad courses that some professors try to avoid. I'm teaching an intro to choreography class to the sophomores. They're so gung-ho. I feel like things have flipped, where they really wanna be pushed.

Tim: What switched in you?

David: I think I mellowed with age and became satisfied with life, and realized that you can't push them without also telling them how fabulous they are. When I first got to UCLA, all I could do was kvetch about how lazy the students were—no rigor. I missed the New York dance community, where everyone worked so hard. I was known as a really mean teacher! Rigor, rigor, rigor! Don't you walk through that door five minuves late! But I realized there must be better ways of reaching them, if I can meet them halfway.

Tim: I have to say, as someone who was given some very blunt, harsh criticism from older folks, both as a writer and a person, I feel like I ultimately benefited from it, and in my own teaching, I've somewhat resisted being overly affirming for its own sake. You?

David: I definitely feel that. I can't tell you the number of times students have asked me, "How did you [become a successful choreographer]?" I said, "Well, I moved to New York and did every job available, had three jobs at once and found I could still rehearse at night. And I never expected to get paid. That's what's called paying your dues." They said, "Oh my God, I could never do that." And I thought, "Well, you probably want to be in another field." Paying your dues is the only way I know. That's why I feel old, 'cause today that rigor can get lost from the equation.

Tim: Right. So you graduated from Princeton in 1981. I think you came close to overlapping there with Michelle Obama, right? She has written in her memoir about feeling very racially alienated there and really only making friends with other people of color. What was it like for you?

David: I left the year she came in. I'd say my experience of being at Princeton is different from my appreciation for it later in life. I hated Princeton with a capital "H" when I was there. I'm from a public school in Texas. I didn't know what a prep school was, I'd never heard of it. But when I was in high school, Princeton sent me an application because I had done well in the era of affirmative action. I was the quintessence of why we have affirmative action. A Black kid in a predominantly white high school who was called the N-word every day. So they sent me an application and my mother said, "Oh my God, I'd do anything if you'd apply." I looked at a map and saw that New Jersey was next to New York, which meant that I could see lots of Broadway shows.

But once I got there, I thought it was racist and incredibly sexist. I did well, but I did not have a good time. But I made some amazing friends and persevered and got out, then went back there to teach in the 1990s in the dance department and started to realize, with distance, "Oh wow, this is just smart kids in the arts—a much bigger world than the one I was there with." And now I can see that Princeton, for better or worse, was the moment that changed my entire existence.

Tim: How so?

David: Because I never would've gone to New York had I not been there as a stepping stone. You see people's faces light up when they know you went there. So it opened doors for me that would not have been opened otherwise.

Tim: How did the racism there manifest? Was it as overt as being called the N-word like you were in high school?

David: No. It was worse. For example, the eating clubs. [Princeton has long had invitation-only exclusive eating clubs that dominate the social scene.] My first scholarship job was serving food at one of them, and it was like I was the colored waiter from the 1930s. They wouldn't say anything outright to me, but [the sense of racism] reeked—it came from their bones. In fact, my very first night at Princeton, I was there early for the program for students who might have a hard time transitioning—a lot of people of color from public schools. I loved the program. But the first night, my dad had just left me in my dorm and I thought, "I can do this—I'm okay. I'm so glad not to be in old racist Texas." And I went to the window of my dorm and someone from across the way called out, "Hey Nigger, I see you." It broke my heart. I thought, "How do I get out of this room without them seeing me?" I sat there for three hours. It didn't even occur to me to go tell the chaperones. Now, to be fair, they were having a cheerleading camp on campus from the local high school, and they were staying in that dorm [and it was probably one of those students who called out the N-word].

Tim: How did you react emotionally to that?

David: It was horrifying. So depressing. Not like "This is going to make me stronger," but more like "The world is no different anywhere." Later, I was able to ask myself, why didn't I say "It's them, not me" and go get my counselor?

By my senior year, academically, I thought I was barely surviving. I thought I was going to get a C in a final course and flunk out. They I got a letter from Princeton: "We are pleased to inform you that you will be graduating magna cum laude." I thought, "What the fuck is magna cum laude?"

Tim: So David—I wanted to be blunt and ask you something. Toward the end of your 2009 piece "Saudade," you deliver a beautiful monologue in the first person about being in a hospital bed in 2007, dying of AIDS, and it's only when your boyfriend comes into the room do you realize that, as beaten down and sick as you are, you want to live because you realize life is beautiful. It's very moving and gets to the heart of that piece's message, which is that life is bittersweet, with joy and agony existing alongside each other. And at one point in the monologue, you call yourself David. So I wanted to be blunt and ask, is that you? Because I couldn't find anything else online that said you were living with HIV.