Sur Rodney (Sur)'s 40+ Years of Caring for Artists and Their Work

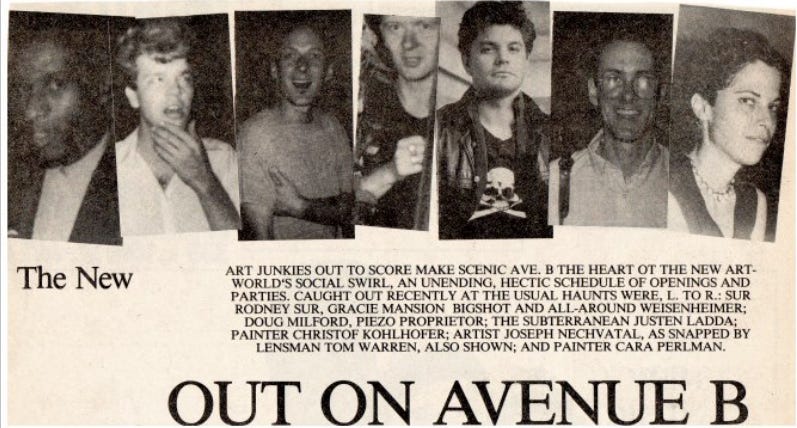

The Montreal-born codirector of the influential 1980s East Village gallery Gracie Mansion is determined to leave all the legacies in his trust in top form.

Hi there, Caftan readers! Spring is coming - yay!

And I have some more good news to share, which is that in Summer 2023, I will have a new novel coming out from Viking called Speech Team. It's about four estranged friends from high school in Massachusetts in the 1980s who slowly drift back together, 25 years later, and realize they were all emotionally abused by the same teacher, who happened to be their speech team coach. So they take a trip together to find him and confront him about the past. And to say more would be to spoil! So I'll just say that it was based partly—but far from entirely—on my own memories of being a [closeted, even to myself] gay kid on speech team in Massachusetts in the 1980s.

Good news aside, I've been feeling angry and heartbroken daily the past month, watching the human toll of Putin's cruel invasion of Ukraine. I made a small donation to humanitarian relief efforts (and you can too) but I still feel pretty helpless. Europe needs to bite the bullet and cut off their addiction to Russian oil!

Thankfully I always have a monthly Caftan interview to develop and take my mind briefly off bad things. I love this month's interview (below). It's with Sur Rodney (Sur), a gallerist, curator and archivist who has been a fixture on the downtown NYC art scene for 40+ years.

I first met—and became intrigued by—Sur Rodney (the "Sur" on both ends of his birth name, Rodney, is short for Surrealism) nearly a decade ago when I wrote this short piece about the very Lucy Van Pelt "Free Advice" booth he was working as part of a retrospective of Black performance art. I was very struck by the gentle and wry advice he gave folks, and have always wanted to do a deeper interview with him.

Well, here it is! And we definitely touch on some topics very dear to my heart that have come up in previous Caftan interviews, such as NYC's downtown queer and art scene of yesteryear, racial dynamics in the world of art and culture, the daily lived experience of gay men in the worst era of AIDS and its aftermath, and—of course—sex!

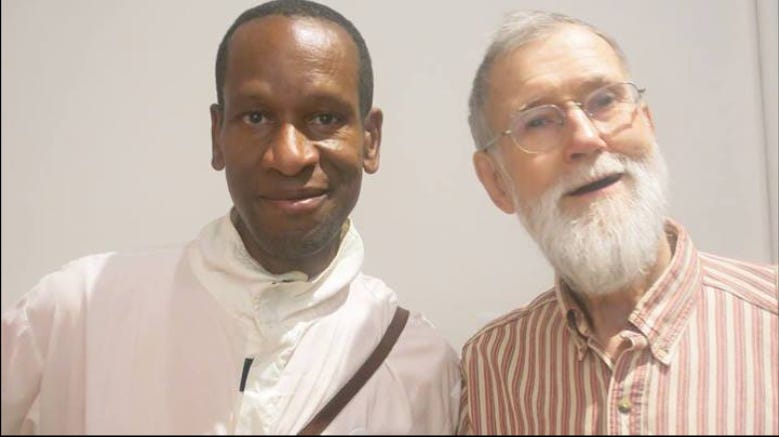

Ever thoughtful, generous and a total open book, Sur Rodney, 68, talked to me one afternoon in late March for four hours, which I think is a Caftan record. I heard about his bohemian Montreal upbringing, his move to NYC and co-directing the influential 1980s gallery Gracie Mansion with his female friend (and one-time wife!) of the same name, his caregiving in the darkest years of AIDS, his eventual entrée into NYC's Black art world, and everything he's done since.

I hope you enjoy our talk. All the photos are pulled from Sur Rodney’s Facebook page, with his permission, unless otherwise indicated. I have some great fellas lined up for future Caftans, so please consider supporting the project with a $5/month subscription to get full access to all the interviews. And if you already do subscribe, thank you as ever for the support. It makes this labor of love possible. Now here we go...

Tim: Hi there, Sur Rodney. Thank you for being open to this today. I want to talk to you about the eighties, the decade you are most associated with, but also about what came before and what has come since.

Sur: I've done so many interviews about what happened to me in the eighties. I think it was a really important decade for a lot of reasons. A lot of my relationship to the artists and situations of the eighties has disappeared because of all the death. I'm one of the people who's still connected to everyone who isn't here anymore, so that keeps me locked into the eighties.

Tim: Right. Actually, before we really dive in, can I ask you: What do you like or hate about interviews, just so I know?

Sur: I like getting something out of interviews, a takeaway—learning something about myself. What I don't like is when they don't get the facts or the names right, or they collapse things together.

Tim: Right. I'm pretty good about that—I've been doing this a long time. But of course I'll always change anything I get wrong.

Sur: You can tell from my previous interviews that I'm pretty candid and open about stuff—sometimes TMI!

Tim: Ha, well, to an interviewer, there's no such thing as TMI. So paint a picture of yourself literally today—describe your surroundings and what you've done since you got up and what you'll do later on.

Sur: Right now I'm sitting in a rocking chair on the ground floor of a townhouse close to Tribeca, surrounded by flat files, work tables, light tables, scanning machines and lots of artwork. This is my work space. I bike over here daily at 7am from the East Village co-op I've had since 1981. This townhouse was owned by my former spouse, Geoffrey Hendricks [the prominent Fluxus artist who died at 86 in 2018].

I was married to Gracie in the eighties for financial and legal reasons. Then in the nineties, we divorced, although we're still the best of friends. Then I partnered with Geoffrey and at some point we decided to get married as a financial arrangement. We were a very tight couple for 23 years. So this townhouse holds his archives and his artwork, and I'm here every day organizing it for a huge deposit at Northwestern University. I've so far done 138 boxes and I have about 80 to go.

So that's what I'm doing here most of the time during the day, in between interviews and writing projects, managing my email and working on my co-op, which I'm the president for. I'm also part of the groups Visual AIDS, What Would an HIV Doula Do? and the gay Black writing workshop Other Countries. I also travel to Montreal, my hometown, quarterly. So that's my life.

Tim: It's amazing you've been in the same East Village apartment since 1981.

Sur: I'm between Avenues C and D, near a lot of community gardens. The area was the center of the drug trade in the 70s and 80s. I felt protected and blended in because it was predominantly Black and Puerto Rican. It was scary for a lot of my white friends. At the time, I had the option of moving from St. Mark's Place to here or to Harlem, and here was easier for me because I couldn't afford to rent a truck to move my stuff to Harlem, whereas here I could just carry it all across Tompkins Square Park.

Tim: Did you inherit Geoffrey's townhouse?

Sur: I share it with his kids, who don't live there. In addition to me, there are two live-in archivists who make sure that the house doesn't burn down. I also have a base income managing the studio of the conceptual artist Lorraine O'Grady three or four days a week. I'm learning stuff every day and I enjoy the material I have to work with.

Tim: Can I ask you, for someone who's been in the East Village so long and witnessed so much happen there—the art scene, the drug scene, AIDS—how much is the past with you on a daily basis?

Sur: The past is the past. I turn on the past when I'm dealing with the past, but I pretty much try to stay in the present. Even how I talk about things in the past changes as time passes. That certainly comes up with the trans[gender] thing now. In the 70s, we'd say "drag queens" or "trannies." You have to be very careful how you use that language now. Back then, we didn't care—we called people all kinds of stuff and it was all fine. But now it's like, whoa, you have to be correct—or expect to be corrected and to apologize.

Tim: Hm, yes. And how do you feel about that?

Sur: I always try to keep up with what's going on now. But with the past, sometimes you have to translate it to what's happening now. For example, back in 2017-18, MoMA did this exhibit on [the iconic East Village 1970s-80s art space] Club 57 and, working with Visual AIDS, they wanted to screen some of the work of a Black performance artist from the time who went by the name Mr. Fashion and who died of AIDS. He once performed with his white roommate who was wearing blackface. The younger Visual AIDS folks were shocked. But they don't understand that in the 80s, we were punks, anti-establishment, thumbing our noses at everything. We were not woke. We were pushing the boundaries. That's what the times were all about, and I have to explain that to them.

Tim: Why do you think young people are like that today?

Sur: Because of the damage—and the history that's associated behind it. Thumbing your nose at the system the way we did then has changed. For example, when we were doing all our stuff in the East Village galleries, we didn't care about [recognition from] The New York Times. We figured they were too stupid to figure out what was going on. So we created our own press—The SoHo Weekly News, The East Village Eye, Today, people are going to target the Times the most.

Tim: You're saying that young artists today want that Times recognition?

Sur: There's very little of what once was "downtown" left.

Tim: But I live near Bushwick and there's quite a young arts and culture scene out here—it's just moved from downtown Manhattan for economic reasons.

Sur: They're all talking to me about this Bushwick thing. Sure, we look at Bushwick and we see a lot of graffiti and murals, just like in the 80s, but back then, we'd just go do it. Now it's all negotiated.

Tim: Well—I see a lot of graffiti that definitely does not look negotiated.

Sur: Years ago, we could afford to spend a lot of time going around and collecting garbage to make stuff. People today don't have that time. They can't afford to be stupid and do things and see what happens, because everyone will record it and know about it within 12 hours. Back then, maybe only 20 people saw the stuff we did. There's a lot to be learned about failing and making mistakes. But people can't afford that anymore, renting a space and doing some crazy stuff. It's less about community now and more about the individual.

Tim: So, to loop back—you don't feel haunted by the past in the East Village?

Sur: Well—I feel very touched by it. I'm working with materials that relate to it every day. But when I'm hanging out in, say, Tompkins Square Park, I'm not thinking about the 80s unless someone asks me.

Tim: Who are you today?

Sur: A flamboyant Black gay man—generous, thoughtful, caring. A bit of a hermit recluse introvert—much more than people think. If I go out and do something, I really have to get charged up for it.

Tim: Where does the introversion come from?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Caftan Chronicles to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.