Stephen McCauley's New Novel Is "You Only Call When You're in Trouble." So I Decided to Call Him.

The modern-day gay Jane Austen, who debuted with "The Object Of My Affection," has an eighth novel out—perhaps his deepest so far.

Happy early Valentine’s Day, Caftaners! And happy February. As I write, sun and blue sky finally appear out my window after a dreadful long NYC streak of chilly gray rain. Perhaps I’ll leave the house after I finish this to go get some of that precious Vitamin D. Is anyone watching Feud: Truman Capote versus The Swans? Do you have a favorite character so far?

I’ve always had a soft spot for Diane Lane (So good in Unfaithful!) and I love the brisk, capable, no-nonsense way she plays Slim Keith (upper left). But I’m also pretty mesmerized by Naomi Watts as Babe Paley (bottom right; that perfect, regal helmet of hair!) and of course Tom Hollander (of Jennifer Coolidge White Lotus “these gays are trying to murder me” fame), who seems to have found a characterization for Tru that feels authentic but is not a carbon copy of the late Philip Seymour Hoffmans’s take in 2005’s Capote. (Hoffman’s Tru actually seems milder than Hollander’s, who seems truly, frighteningly malevolent.) Of course, I’ll watch anything set in NYC between 1960 and 1990 with great hair, makeup, clothes and interiors, and this Feud definitely qualifies in that regard.

Before we dive in, I have two obnoxious requests. The first: I’m super grateful to anyone reading this who’s bought a copy of my latest novel, Speech Team, since it came out in August, but if you haven’t, would you consider doing so? (It’s only $14.99 right now on Amazon!) Or we can do it this way: If you want a signed copy, email me at timmurphynycwriter@gmail.com and say so, and once you Venmo me $25 (the cost of the book plus shipping), I will order it from Amazon (no, I don’t have a huge free stash to draw from), sign it for you and send it to you. I make this obnoxious pitch yet again because at this point I’m halfway to what the publisher would consider a sales count that justifies picking up my next book—and I do want to get that next one out there in the world because I really like it! (Hint: It’s set in a very romantic city that is not New York.)

The second obnoxious request comes prefaced with a huge THANK YOU as usual to everyone who’s pay-subscribed to Caftan. The request is that those of you who haven’t, who truly enjoy Caftan every month, consider upgrading to the $5/month version. The reason is that, other than writing novels, Caftan is my favorite thing to work on and I would aim to post as much as weekly I could take more time away from my other paid writing work—and I could do that if I could, say, double my pay subscriptions at this point.

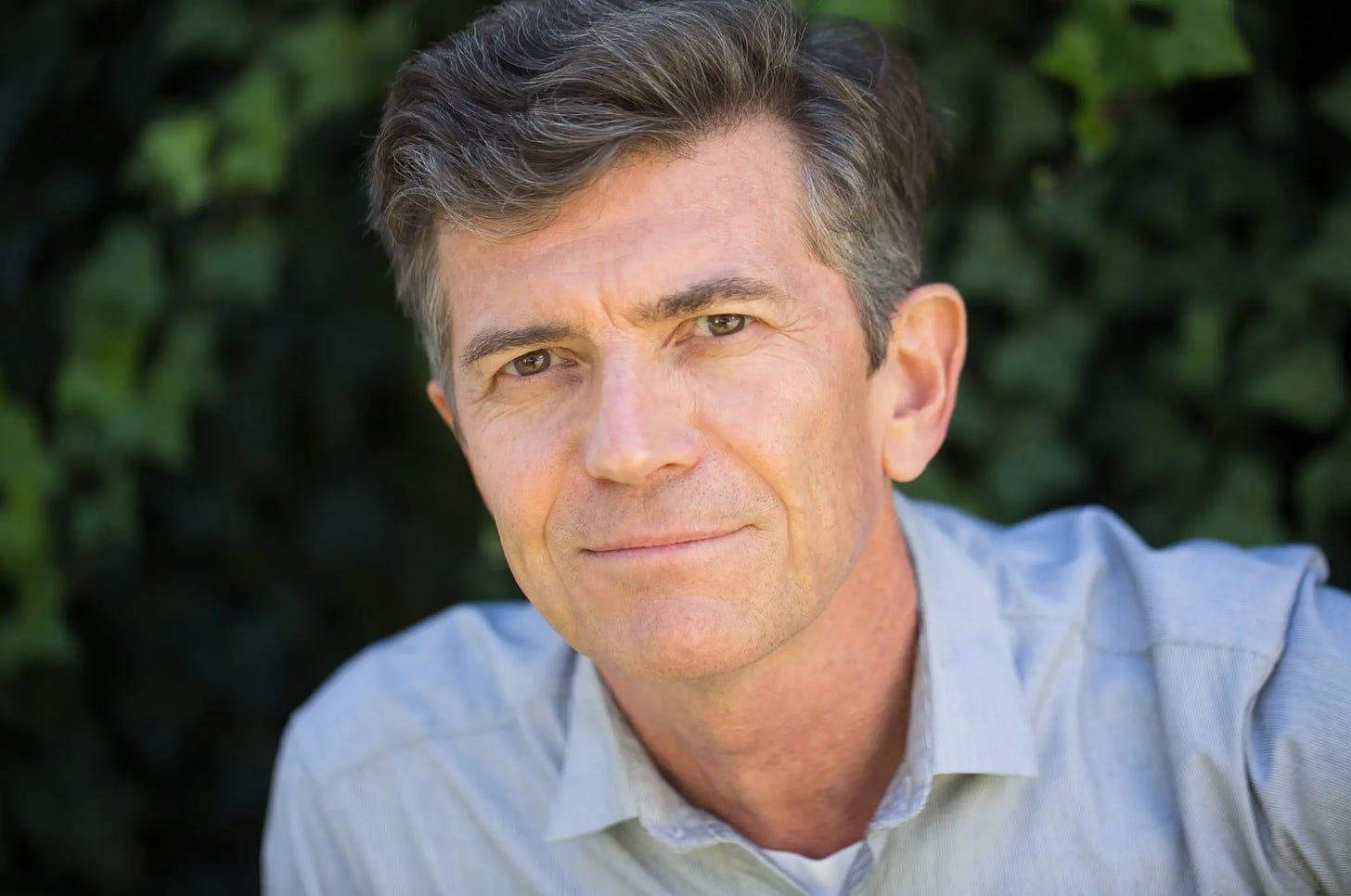

Okay! I’ve checked my obnoxious boxes and can now tell you a bit about this month’s interview, which is with the Boston-based longtime novelist Stephen McCauley, whose 1987 debut, The Object of My Affection, you’ve perhaps read or have at least heard of because of the very sweet 1998 movie version with Jennifer Aniston and Paul Rudd.

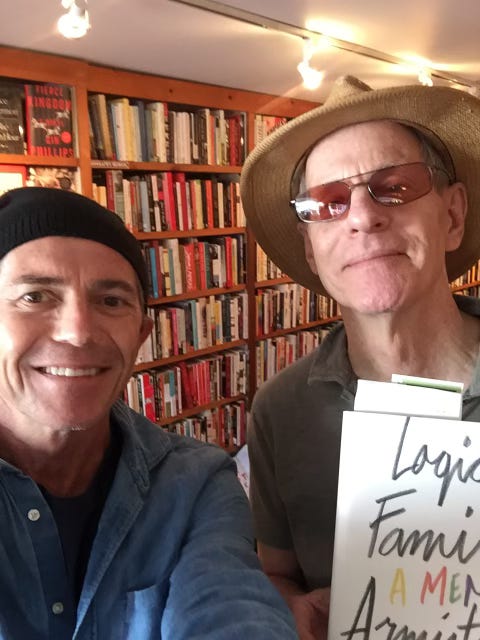

I love Stephen. I met him at the Provincetown Book Festival in 2018, where I interviewed him about his then-new novel, My Ex-Life. (Here we are!…)

Now his eighth novel is out: You Only Call When You’re In Trouble.

It’s about, as are basically all Stephen’s novels, a somewhat J. Alfred Prufrock-like Boston-area middle-age gay man with a compromised love life and at least one deeply meaningful but extremely complicated platonic relationship with a straight woman. In this case, the middle-age gay man is fussy architect Tom, and the women in question are his sister, Dorothy, and niece, Cecily, both of whom drain the life out of him, albeit in very different ways. In my recollection, this might be Stephen’s deepest and darkest novel so far—there is something particularly pathos-ridden about the way that poor Dorothy is drawn, not to mention how Tom just can’t stop caring for her no matter how hard he tries to break away.

But I’m sure that any of you who read Stephen will agree that the main reason we read him is for his oh, so dry, eviscerate-me-with-a-quill Jane Austen wit. Few contemporary authors have such a way with a devastatingly shady aphorism or observation. Here’s a bit of classic McCauley from the latest book:

Tom had learned that an important part of aging with dignity was pretending you had no sex life and didn’t want one. The public had grown used to open declarations of racism, the details of frequent mass shootings, gruesome images of gastric bypass surgery that played on TV for entertainment value. The one thing no one could stand to hear about was the sexual desire, never mind the sexual activity, of someone in their sixties.

Or this:

Consistency was one of those minor qualities you appreciate in someone only if you can’t find something better to praise. It was like praising someone for knowing how to tie a bow tie.

Or this:

She’d always been suspicious of ambition. It was often adjacent to ruthlessness and sociopathy.

I love that Stephen’s books have that kind of hilariously judge-y Jane Austen or Edith Wharton vibe but are still so decidedly contemporary, concerning themselves as they do almost always with liberal, arty-bookish northeasterners. Along with Michael Cunningham’s A Home at the End of the World and David Leavitt’s The Lost Language of Cranes, The Object of My Affection was one of the first openly gay novels by an openly gay writer that I read in college that made me believe that maybe there was a place in the world going forward for gay stories—as long as they were well told. So I’m kind of indebted to Stephen, who, as you’ll see I bring up in the interview, had an upbringing very similar to my own. And, honestly, Stephen, who is almost as hilariously self-deprecating as Joan Rivers, ended up being far more candid about many things in this interview than I expected—including, well, sex in one’s sixties. (Yes, he is more than having it.)

You Only Call When You’re In Trouble is not only very brisk and funny and melancholically moving, it’s also eventful. Hapless Dorothy is about to drive off a medical and financial cliff, her relatively well-adjusted professor daughter Cecily is fending off a sexual harassment claim from a young female student, and poor, exasperated Tom is facing both the end of his longterm relationship and his career. So I’m not going to give any spoilers, because a lot happens in these 322 pages, set both in the Boston area and in Woodstock, New York. (Stephen’s depictions of the town’s aging hippies is priceless.)

I’ll just hope you enjoy the interview and then check out the book. So here we go… (and thanks to Stephen for the photos he dug up, like this one of his twinkish self from the late 1970s:

Tim: Stephen, thanks so much for talking to me today. Can you start by telling me what a typical day is like for you?

Stephen: I wake up pretty early, around seven. I live in Cambridge, Mass., with my partner—we're not married—named Sebastian Stuart.

He's a writer who's written a number of novels in different genres and has also written a memoir published by Querelle Press called What Wasn't I Thinking? It focuses on his relationship with his cousin, who was this very beautiful young woman whom he had this real bond with who became schizophrenic. But it's also about his grandfather who died before they met, a very famous anthropologist named Bronislaw Malinowski—

Tim: Oh, wow. That is a very famous anthropologist.

Stephen: Yes, a big name. And the impact of having this quote-unquote "great man" in the family. So I met Sebastian over 30 years ago. He's a native New Yorker and we met at a writing colony in Vermont, and then he moved to Boston.

Tim: What has it been like being in a relationship for so long with another writer? I don't know if I could do that. Is there competition and rivalry?

Stephen: It's been fine. We have very different writing processes, for one thing. He's much more spontaneous than I am in terms of his writing—probably in everything.

Tim: Meaning what?

Stephen: I'm very self-critical. It takes me a long time to write books because I edit a lot and overthink. I have stacks and stacks of notebooks full of material that doesn't end up in the novel. And he's more fluid, a lot of which I think comes from his having written plays. Most of the people I know who write plays do so more quickly than if they were writing novels.

Tim: So there's no jealousy or competitiveness?

Stephen: He's extraordinarily generous and supportive of me, and that makes me want to be the same way toward him. That's probably not a satisfying answer. It's probably disingenuous as well.

Tim: No! I mean, if it's true, it's true. And that's great. Maybe it's so because you're not both writing in the same space—in your case, literary fiction.

Stephen: It's possible, but his first novel was a thriller published by Bantam. But also my whole relationship to the question of envy and jealousy about other writers has definitely changed over time. I was talking a couple of weeks ago with this young woman whose first book is coming out. She asked me how writing was different for me than it used to be, and I said that I don't feel the same kind of competitiveness or— it literally feels better on a physical level to celebrate somebody else's success rather than stew in resentment. I think some of that has to do with age. I've let go of a lot of expectations I might've had when I was younger. This comes up in my new novel as well: Do you have a right to want to have success at a certain age, or are you supposed to step aside and let the next generation have their moment?

Tim: Um, yeah. For me, even if I personally dislike or resent a writer for some reason, if their work is good and gives me pleasure, I have to give it up to them. Does that make sense?

Stephen: Yeah. If a book is working for you, to deny yourself the pleasure of enjoying it because it's a bestseller or won prizes or whatever seems kind of self-defeating.

Tim: Exactly. So can you describe your house?

Stephen: It's a condo in a brick building that I think was built in 1902 and it's pretty roomy. It's three bedrooms but one is very small, so we actually have one bedroom and two studies. Almost everything in here is from one of our families and if not, it's thrift stuff. Sebastian collects paintings, so a lot of the artwork is from thrift stores or garage sales he'd find when he had a house in the Hudson Valley.

Tim: Okay, so you usually get up around seven.

Stephen: And I go into my study and read for maybe an hour—whatever novel I'm reading. Right now I'm reading River East, River West, a new novel by Aube Rey Lescure. It turns out she and I live in the same building! It's about a woman in the early 2000s whose mother is white American and whose father is Chinese.

Tim: Do you make coffee first?

Stephen: I make tea first. I'm also reading—and this is totally my comfort zone of reading—the Virago Modern Classics collection, which are reprints of these mostly British women writers mainly between 1990 and WWII, authors like Elisabeth Russell Taylor and Olivia Manning. And the book I'm reading now is The Way Things Are by E.M. Delafield, who also wrote The Diary of a Provincial Lady. These are mostly domestic novels with a certain kind of witty British writerly voice that's very close-up on characters, without a lot of huge events.

Tim: They sound very you, based on your novels. So that sounds like a nice way to start the day.

Stephen: After, I make juice with my vegetable juicer and then I get out of the house, which is really important to me. I've been going to the Cambridge Public Library and spending the whole day there. Which is not to suggest that I'm writing for eight hours. Or I go to my office at Brandeis [where he is co-director of the creative writing program] and do a little school-related work there and a little writing, plus some yoga on my yoga mat. I spend some time gossiping with colleagues and I also try to go out and walk for at least an hour. I stopped going to the gym during the pandemic and frankly I'm not dying to get back. I've been doing yoga since I was a teenager.

After that I go home and cook dinner for us. I'm adamantly not a recipe person. I'm sort of baffled by people who do that, mostly because it seems so disciplined and rigid. I just open the fridge and see what's there. My favorite thing is to prepare a really big fresh salad with some kind of unexpected ingredient in it or a delicious dressing that I make. Sebastian and I eat together almost every night. Then after that, my favorite thing to watch on TV is cult documentaries.

Tim: Oh, yeah? Did you watch the ones on that NXIVM cult?

Stephen: That one I didn't like so much. The best one is called Wild Wild Country, about the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh cult.

Tim: Cults give me an ick feeling.

Stephen: That's why I like them. I like the ick feeling, and thinking, "Oh, I would never fall for that." In every cult, there is always an element of control over people—people who want to have every hour of their day accounted for and dictated by someone else. And there's always some element of furtive power abuse involving sex.

Tim: Is there a weird part of you that wants to be in a cult?

Stephen: No fucking way. But to be a cult leader? One-hundred percent. Who wouldn't?

Tim: And when do you go to bed?

Stephen: Somewhere between eleven and twelve. I'm not a good sleeper. In my family it was considered an insult to tell someone they were a good sleeper. I think there's something shameful about sleeping well.

Tim: Ha, well that's a great segue into asking you about your childhood. I actually deduce that we have very similar backgrounds—growing up Irish Catholic in a middle-class Boston suburb with a rather, um, unaffectionate and sardonic Irish father. Would that be correct?

Stephen: I think we talked about this years ago when we did our Provincetown talk. My father was a cranky, basically unhappy Irish guy for whom, like a lot of men of his generation, the best years of his life were when he was in the military. Getting out of that into civilian life was a difficult transition. To be honest, my parents didn't have a happy marriage. My mother was Italian and I was raised by her family.

Tim: That's another point of commonality, because my mother is Lebanese and all the "family" was on that side of the family, with actually very little family on my father's side, whom we saw much less often. And the Lebanese side is quite loud and crowded and demonstrative and a bit crazy, with a lot of it revolving around food.

Stephen: Yeah, totally. The Irish side lived a ten-minute walk from us and we'd see them for fifteen minutes once or twice a year. But I had this sense of not knowing quite who I was, like an outsider, which I'm sure had to do with, even when I was very young on some incoherent level, that I was gay. It wasn't an unhappy childhood. It was a white middle-class suburban upbringing at a time when life for that particular demographic was about as good as it ever got. So to complain about it seems ungrateful.

Tim: How do you think your upbringing shaped you?

Stephen: I think the biggest impact for me is always feeling a little bit like I don't belong. Even things like reading—ever since I was a kid, I loved reading in a family where nobody read for pleasure, and it was kind of considered weird of me and even a little bit suspect. Honestly, it was kind of discouraged. "Why don't you come out here and watch TV with the rest of us?" So, this feeling of not quite belonging. I've been teaching since 1987 and I've never felt like I belonged in academia. But basically that's how it needs to be for me.

Tim: Who shaped you the most when you were a child?

Stephen: My sixth grade teacher, who would recommend books like Johnny Tremain, as well as Steinbeck. There was one bookstore in [his hometown of] Woburn that mostly sold greeting cards but also racks of paperbacks. I thought, "Well, if a book is selling a lot, that means it's really good." So I read potboilers like James Michener or Arthur Hailey's Airport.

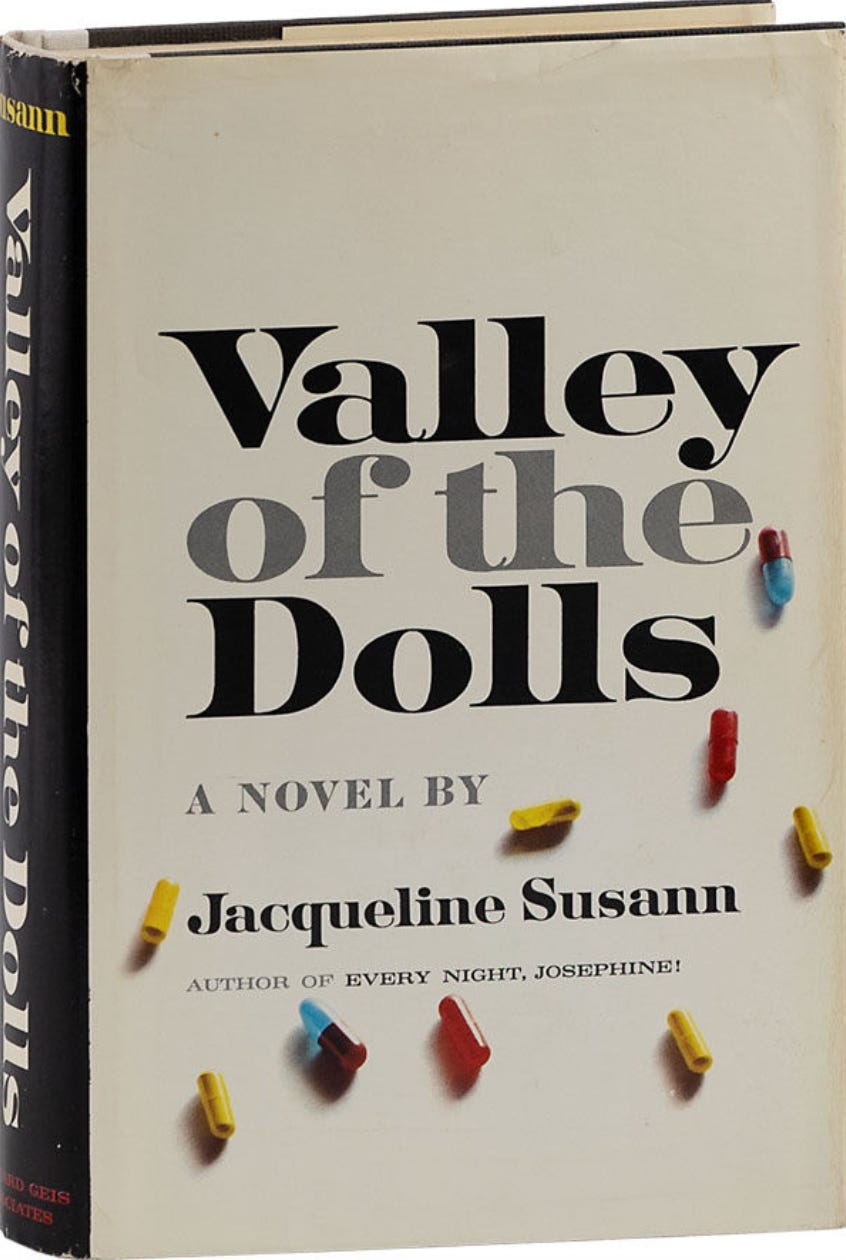

Tim: Ha, we both started with potboilers. The first big "grown-up" book I ever read, at age 11, was Gone With the Wind, because my aunt, who was a real chain-smoking broad who loved her steamy pulp fiction, threw it to me one night because she knew I was bored. She very inadvertently launched my whole life of reading, and then writing, big fat eventful novels. When I reread GWTW in college, it was fully impressed upon me how insanely racist it is, but at eleven, I was sort of intoxicated by how huge it was—so many characters, so many relationships, sumptuous descriptions of everything, so many twists and turns over so many years. And in fact I think I read this interview with you where you said the only book everyone in your family read was Valley of the Dolls.

Stephen: We had exactly the same upbringing, because I had this aunt who was also a real broad, tall and thin and she smoked Tareytons and she used to read stacks of books and then give them to my mother who wouldn't read them, except for Valley of the Dolls.

Tim: Okay, so what were you like as a teenager in the sixties and seventies? Did anyone know you were gay, including yourself?

Stephen: Nobody knew anyone was gay then unless you were really flamboyant. I was extremely introverted and tried very diligently to be invisible, and luckily I think I succeeded.

Tim: Did you have friends?

Stephen: Some, but not many. A lot of my afterschool life revolved around biking around Concord and Lexington and Cambridge. I was very solitary. Then I went to the University of Vermont and that's where I came out, even though Burlington, Vermont in the mid-seventies was not a particularly gay environment.

Tim: Whom did you come out to?

Stephen: My college roommate. I didn't come out to lots of friends right away. But I began having an affair with one of my professors. In the seventies, that wasn't such a big thing. And then I went home to Boston for the summer and my mother read a piece of mail from this [professor] guy and confronted me. "I think this person is more than a friend," she said. So I said, "Yeah, well, I'm a homosexual." And she said, "So what you're saying is you're a faggot." And it went downhill from there.

Tim: What happened?

Stephen: It just went downhill and I ended up having to leave, basically. So I went back to Burlington and the professor said that I could move in with him.