Matthew Bank on the Rise and Fall of the Great 1990s-2000s NYC Gay Rag HX

The free weekly club mag was the bible of the "gay nineties" in Chelsea—but digital and gay lifestyle changes post-9/11 led to its downfall.

Hi folks! For those of you in cold climes, I hope you’re surviving the doldrums of winter. And, as ever, I’d like to thank both paying and nonpaying subscribers for all the love and support for The Caftan Chronicles. Please tell friends about it if you like it and please consider getting the $5/month subscription if you haven’t already—it really helps me keep this alive amid my other jobs. Also: I am always looking for gay men over the age of 60 who have an important slice of gay history to share—particularly outside of NYC. If you have ideas for future interviews, please drop me a line at timmurphynycwriter@gmail.com.

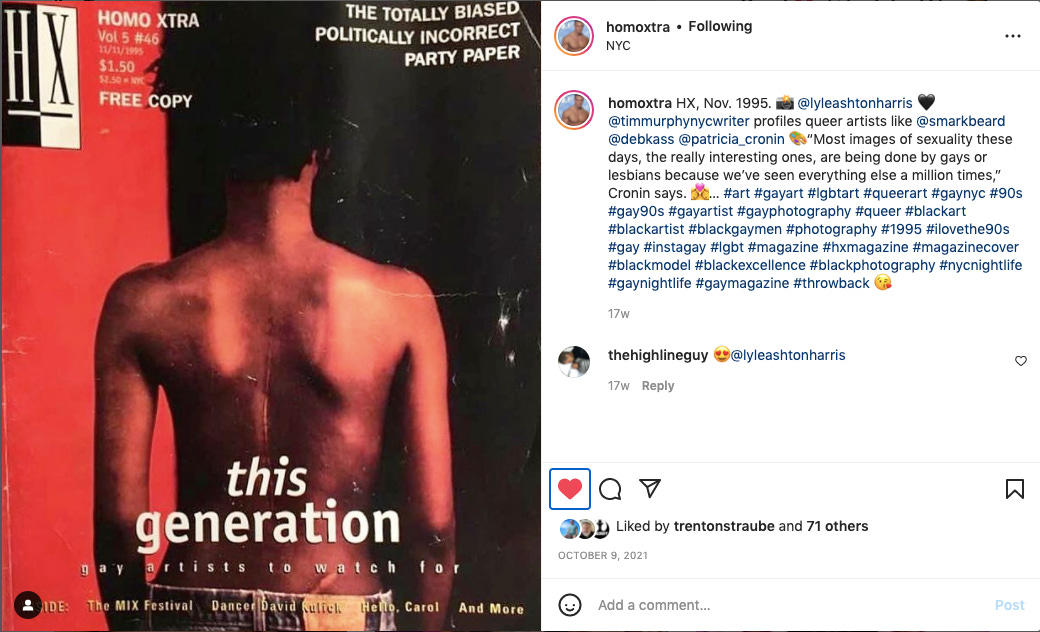

I have a personal connection to this month’s interview. I’ve long worked at or written for magazines, but as it happens, my first magazine job in NYC, in 1995-6, was as the editor of the free weekly gay club rag HX. I lasted less than a year there, but for much of that year, I had a blast, interviewing an incredible array of gay visual artists, designers, entrepreneurs, musicians, nightlife personalities and activists. For example, I loved working on this Fall 1995 issue for which I interviewed—and we featured the newish work of—queer artists including Lyle Ashton Harris, Mark Beard, Tony Feher (d. 2016), Deborah Kass, Patricia Cronin and more…

Working at HX plunged me into gay nightlife and culture in a way I hadn’t been yet and it charged my adrenaline with the rough-and -tumble task of putting out a weekly rag—which I vividly remember littering the streets outside every gay club and bar in Chelsea come Friday night. “I’m walking all over my own workweek!” I’d lament to friends (or a trick) as we left Sound Factory Bar at 4am. And I loved working alongside Brian Gately and Austin Downey, both of whom I’m still in touch with, in our little ragtag editorial corner of the office where we would kiki and laugh about stupid, funny things all day.

HX started in 1991 and ended in 2009. It’s an incredible archive of gay life, pop culture, music, fashion, sexual mores and even (somewhat tangentially) politics and social issues from those decades. It’s also a reminder of how narrow mainstream gay life was then—if you weren’t white, young and muscled, there wasn’t much space for you to be represented in HX as a model. It’s the main reason I left—I just couldn’t get the support I wanted to show aspects of gay life outside of the muscle culture of Chelsea. Every time I wanted to put, say, bears or voguers or Jackson Heights or Washington Heights on the cover, I was reminded that there was another muscle-queen-driven circuit party advertising with us that we had to promote.

Nonetheless, I still get nostalgic when I look through my old issues and think about that time. The house music was so good, the drag queens were fierce, and there was always someplace to go—often several—every night of the week. Delightfully, you can now look at a growing number of HX’s nearly 1,000 covers on the HX memorial Instagram, which is where I sourced all the covers you’ll see here.

So I was delighted and honored when HX’s cofounder Matthew Bank—who now co-owns Bank Neary real estate—agreed to tell me the entire HX story as he remembers it. (I should also note that Matthew, not yet being 60+, is a Caftan interview exception.)

So join us! I think the chat will especially engage you if you remember this time and place. Put on your black leather Skechers boots with the stripes around the soles, cue up the Frankie Knuckles or Junior Vasquez on the old vinyl, make yourself a Cosmopolitan…and here we go!

Tim: Hey Matthew! I'm so excited to talk about HX with you. But first let me ask you what you're up to on this snowy Sunday in late January 2022.

Matthew: So today, as always, my French bulldog Hazel woke me up here in the Bronx between seven and eight and wanted to go out for a walk. So I put on lots of warm clothes and then put her into her snow suit and boots and we walked to the park across the streets, where she peed and pooped quickly and dragged me home because she doesn't like the snow on the ground. I did some housecleaning and some unpacking, as I just moved. Then I texted some folks to see if they'd watch Hazel while I did some showings downtown, then took Hazel to one of their places next door. Then I met some clients over by Hudson Yards to look at a big, bright cool loft in an old factory building. Then I drove to Brooklyn Heights to show an apartment there. Then drove back up here, picked up Hazel and have just been here returning emails. And now we're talking!

Tim: Yes, we are. So—um, you were born in Westchester?

Matthew: Manhattan, actually. My parents met when they were in grad school at Columbia in the 1950s—my dad was a professor of secondary education and supervised student teachers in the NYC school system, and my mom was a teacher who, as happened back then with women, was fired when she got pregnant, so she ended up working for my uncle, who was head of statistics at a state psychiatric research center in Rockland County.

But we moved out of the city in 1969 when I was three because the crime on the Upper West Side was really bad and my babysitter was mugged at knifepoint with me in tow inside our apartment building, so we followed my uncle to Larchmont in Westchester.

Tim: Where Joan Rivers was from! What were you like as a child?

Matthew: Nerdy. I literally did nothing but read from a very young age. I was not interested in sports or playing with other children.

Tim: As a future magazine founder, were you into magazines?

Matthew: Later on. I was also really interested in cars and stereos and music—those were things my father and I could talk about together. I became obsessed with Mercedes when my uncle bought one, and I now have one for myself.

Tim: When did you have your first inklings you were gay?

Matthew: In first or second grade, I vividly remember being outside in gym class and noticing one boy who was wearing shorts and having this desire to see him naked. I was like, "Huh? What does that mean?" It stuck with me for a long time. I was too scared to find books on homosexuality at the library—I was afraid someone would notice. I finally did though, at about age eight. I immediately realized it was a very bad thing and became depressed and sad, because I'd had this romantic notion that I was going to succeed at heterosexual marriage where my parents, who had divorced, had failed. I sat around and moped quite a while. "What's wrong with you?" my mom was constantly asking. She half-threatened to send me to a psychologist. I decided to pretend that my gayness wasn't going to exist and nobody was going to find out.

Tim: Jump to when you came out.

Matthew: In junior high school, I gravitated toward this misfit group of kids in the chorus. One of them, a boy, had a copy of the 1979 play "Bent" by Martin Sherman about gays during the Holocaust. He showed it to me. "Have you ever heard of this?" he asked. "Is this the kind of thing you're interested in?" I was like, "Yes, it is." And we had this mutual coming-out moment but we didn't tell anyone else. I'm actually still in touch with him. He lives in Palm Springs with his husband and I saw them last year.

Tim: Okay, so tell me what starts leading up to the start of HX in 1991.

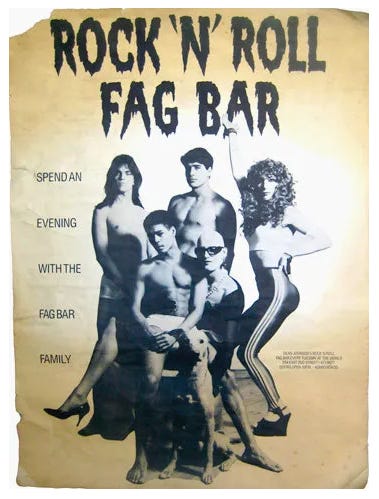

Matthew: I went to Harvard in the mid-eighties and studied art and ran the gay student groups and put on gay parties—at a time when there were still very few out students. I wanted to get out of Boston the day after graduation, so I moved back to NYC where I'd gotten a job at MoMA working as an assistant to one of the curators in the painting and sculpture department, which was an amazing job. I had a bunch of friends from college here in NYC and was going out a lot—and the thing everybody did was go to the Monday night ACT UP meetings. That was part of our weekly late-eighties scene: Mondays at ACT UP, Tuesdays at Rock 'n' Roll Fag Bar at World—also Boy Bar and Uncle Charlie's.

I participated lightly in some ACT UP protests and I met some people who were sick or HIV-positive. It was a very scary time and I felt like ACT UP was something I had to be a part of, even though I'm not a scream-and-get-arrested type.

Then ACT UP announced they were going to have an art auction fundraiser and they wanted someone to head the committee. I thought, "I work at MoMA—I can do this." I solicited donations from a bunch of great artists and after the auction, they said, "Let's have a standing fundraising committee." And it was there I first met the gay club promoter Marc Berkley (who died at age 56 in 2010) and that's what started the whole HX thing.

Tim: Marc was a really larger-than-life character on the gay club scene in the nineties. What was your first impression of him?

Matthew: I knew his name because he'd been a promoter during the eighties. He said to us, "One of my best friends just died of AIDS and I want to do something in his honor, so I've arranged to have a Grace Jones concert at Palladium as a benefit—do you want to help organize it and get all the money?" Of course we did. This was 1989, maybe late 1988. I thought of Marc, "This person is really exciting and interesting—I like him." He was about ten years older than me and he had a million interesting stories.

His friends were all in relationships and he didn't like to be alone, so after we worked on organizing an event, he'd say, "Do you want to go out to dinner and then come with me to these three clubs?" So, as a platonic friend, I did. He didn't like to spend a lot of money on food. He liked to go to diners and order a five-course meal, then we'd go to whatever was open. "Tonight they're doing a party at The Underground [where the Union Square Petco is now], then it's Thursday, so we should go to Area." There'd be something at Irving Plaza that [promoter] Chip Duckett was doing, Sugar Babies, Flamingo, Mars on Sunday—there were tons of gay nights everywhere you went. We'd go to each club for an hour. At that point, he didn't drink or do drugs, so we'd drive from club to club and then he'd drive me home.

Tim: How did nightlife intersect with AIDS?

Matthew: A lot of the people I met at ACT UP, who were more of an East Village crowd, were going out—The Bar, Tunnel Bar, Boy Bar, The Boiler Room. AIDS-wise, I was terrified. I don't think I had sex with anyone during that time. It was a very weird and very bad time.

Tim: Right. Okay, so back to HX...

Matthew: So at this time I was going to grad school in photography at SVA and started doing graphic design to make money after I left MoMA because my crazy boss fired me. I started doing club invite design. I bought an Apple IIfx and a laser printer, which together cost me $11,000, but that's how I made a living. I was living in my grandparents' apartment in Chelsea with my grandfather, because my grandmother had died and my grandfather was developing dementia and my family asked me to move in with him to be with him at night when the home care was not there.

So at this time [club king] Peter Gatien was on the upswing with the clubs Limelight, Palladium and Tunnel, and he hired Marc at Limelight, who connected me to Peter, so I started doing club invites for all the other Gatien club promoters, like Michael Alig.

Tim: Oh, wow. What was Alig like?

Matthew: Businesslike but completely nuts. But this was before all the crazy drugs, just when his night Disco 2000 was starting.

Tim: What were the club drugs at this time, the very early nineties? Mainly Ecstasy? X?

Matthew: I didn't take drugs or drink but, yeah, Ecstasy was the drug that was happening, then Special K [ketamine] when you started coming down from X. Crystal meth did not come into the scene until a few years later.

So I was designing the club invites and meeting a lot of people. March was the kind of person who would talk a mile a minute and had 100 ideas every day. One day he says, "We should start a magazine." Most of his ideas I thought were crazy, but this time I said, "Hm, that would be fun—what do you mean?" He said, "When you open a club night, there's nowhere you can read about it, especially in advance of its opening." At the time, the New York Native, a gay newspaper, devoted half a page to nightlife with a list of bars that was three yeas out of date.

Tim: Didn't Michael Musto in The Village Voice write about nightlife?

Matthew: Yeah, but only after a place opened—not what was coming up. And you couldn't afford to take out an ad in The Voice, it was too expensive.

Tim: So how did you open a gay night?

Matthew: Sometimes you hooked up with a promoter who had a mailing list, but that was expensive. [Rival gay promoter] John Blair had the biggest list—that was his bread and butter. But otherwise you'd stand outside a club night similar to what you were opening and hand out invites. Promoters would actually put their initials on their invites and get paid by the club $1 per person who showed up with their invites.

So Marc said, "Why don't we publish a pocket-size gay club guide and hand them out as people leave clubs?" So that was the germ of the business model. We were hiring waifs off the street who got paid by the hour, maybe $10 an hour. Sometimes we'd do it ourselves.

For the first issue, which came out September 1991, I was able to do all the things we needed—I could write and edit and I had a laser printer. The content was a list of bars and clubs, a night-by-night calendar and a little gossip section. One of the first things on the calendar was the opening of [now defunct Chelsea gay bar] Splash, which was like nothing anyone had ever seen. It was huge with a gigantic bar and of course the showers [under which go-go boys would dance]. So it was Labor Day weekend and we distributed it at Wigstock, which was in Union Square that year.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Caftan Chronicles to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.