Jearld Moldenhauer Helped Launch the Gay Movement in Canada and Then Started the Glad Day Bookshops

The man who now tends birds and plants in Fez, Morocco, started several gay institutions in Toronto and Boston in the 20th century's final three decades.

Hi there, Caftan readers—it’s spring! As I write this, sadly, I’m about to get up soon and go to a protest here in NYC against the news, just leaked, that the U.S. Supreme Court will likely overturn Roe v. Wade. I knew this news was coming, but it’s still shocking that something that has been settled law in the U.S. for almost 50 years is about to disappear. It’s a reminder that societies swing left and right over the years, that rights and freedoms are not givens and have to be constantly defended and fought for, and are sometimes (hopefully temporarily) lost. I, like many, wonder if the U.S. is really sliding into a kind of Handmaid’s Tale theocracy after what has been on the whole the decades-long expansion of rights for women, LGBTQ people and other groups.

It certainly makes me think about the U.S. vis-a-vis our northern neighbor, Canada, whose own LGBTQ movement history I admit I’ve known precious little about. So when someone suggested I reach out to Jearld Moldenhauer, I was interested. At 75, he’s lived the past many years at Dar Balmira, a beautiful old house in Fez, Morocco, where he has created a gallery for his photography and a lush rooftop garden…

But at the start of the 1970s, he moved from his native upstate New York to Toronto—he’ll explain why below—and became a key figure in the development of the gay community in that country, which sorta kinda decriminalized gay sex in 1969. That was the start of decades of pro-LGBTQ legislation in that country, which often preceded similar laws here. (Marriage equality, for example, became Canada’s law of the land in 2005—and ours in 2015. Canada’s Supreme Court banned LGBTQ discrimination in 1995; ours didn’t pass something comparable until 2020.)

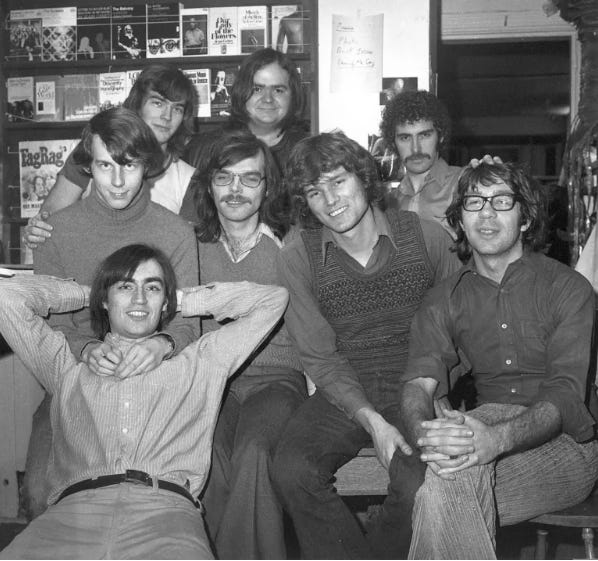

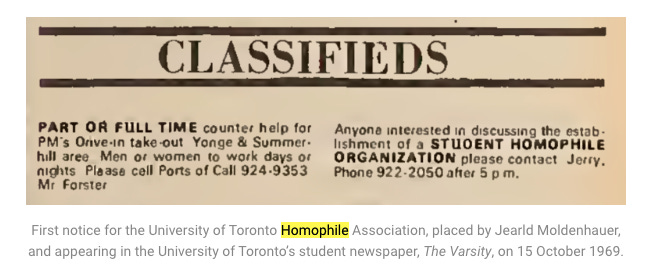

In the early 1970s, Moldenhauer started not only apparently the first open Canadian campus gay group, at the University of Toronto (where he worked, not studied)…

…but then The Body Politic newspaper, which eventually morphed into the current Xtra, and also the queer Glad Day Bookstore—first in Toronto in 1970, then in Boston in 1979. (The Toronto store, no longer tied to Moldenhauer, is still going; the Boston one—which I remember well, having grown up outside the city—closed in 2000.) He began his transition to Morocco in the mid-2000s. And now he wants to move to the Phillippines to open a nature sanctuary!

Jearld and I Zoomed twice, for a total of four hours, and as you will soon see, we clashed on some issues that popped up in the conversation. I don’t share his beliefs about man-boy love being okay or about transgender people not being legit.

I was left asking myself on what ground we actually met, and I would have to say it is our shared experience that the printed word—in books and magazines—was so fundamental to our coming into a sense of our gayness, of its place in history and on the spectrum of the human experience. When I think of books like Dancer from the Dance, A Boy’s Own Story, or Another Country, or of magazines like After Dark or The Advocate or Christopher Street, I think of the sustenance I took from them, learning that I was not alone in my gayness but a part of something bigger—something, in fact, quite beautiful, artistic and fabulous.

Books played this same role for Jearld, and it means so much to me that he put in the time and effort to make these kinds of titles, once shunned by mainstream retailers, available both in Canada (often in the face of extraordinary censorship in the 1980s) and the U.S. The interview with him was a reminder that people are often made up of conflicting parts and that you can’t throw the gayby out with the bathwater, so to speak.

I hope you enjoy this chat with Jearld. If you already subscribe to The Caftan Chronicles for $5/month, thank you! You can read the whole thing. If you don’t, I hope what I’ve put in front of the paywall will entice you to subscribe. I must say, I am very excited about my June interview—I’ll be chatting with a genuine idol of my literary heart, who has a heartbreakingly beautiful new book coming out. (I just finished it—it wrecked me…in the best way!)

Until then, Happy Spring! And think about what you can do—donate? canvass? make calls?—to help make the November midterms less of a shitshow for what’s left of our democracy.

Tim: Hi there, Jearld. Thanks for agreeing to talk. So, can you start by telling us a bit about how you ended up in Fez and what your life is like there? I see countless books behind you on our Zoom call. Are they all yours?

Jearld: Well, I was a bookseller, so I had thousands of books but I brought only about 300 or so with me. But as for my house in Fez, you would never find it. The streets around here are meant for donkeys, not vehicles, and they're so narrow that Google satellite devices don't pick them up.

Tim: So, you moved there four years ago?

Jearld: I actually bought the house, Dar Balmira, in 2006. I co-owned a house in Toronto with another man, but we sold it in 2017 because he had health issues. I've traveled all my life. I used to go away for two or three months a year. As for how I ended up here, I had a close friend in Barcelona who'd traveled a lot here. And of course I'd read some of books of Paul Bowles, who lived here for 40 years. I visited him on my first trip here in 1985. Around 2006, I decided to rent an apartment here and look at houses at the same time. At that time, a lot of foreigners were buying up these old houses. I looked at 40 or 50 and this was one was in pretty good condition but still needed a lot of restoration work. My best guess is that the house is 100 to 150 years old.

Tim: How big is it?

Jearld: There are four large salons on the two main floors, but between those floors, there are smaller floors where the ceilings are only eight feet high, where the bedrooms are. Fez was founded in the ninth century because of the abundance of fresh water from a river in the middle of two hills. I'm on the less touristic side of these hills. A lot of restoration work was done in my neighborhood during the two years of the pandemic. Tourism is very important here, and the streets are once again filled with tourists.

Tim: Do you have access to healthcare?

Jearld: The healthcare here is very bad I got my COVID shots free from the government, but there isn't really primary care and it's hard to find a doctor that really knows their stuff. Recently, I had to get a health certificate to get my residency renewed, and the doctor put the stethoscope on my chest and assured me that I was alive and then asked for his money and gave me the paper I needed.

Tim: Why do you choose to live there?

Jearld: One obvious reason is the weather. As you get older, Canadian winters steal five months of your life. I also like the social life here. I'm an outsider here and I'm not fluent in Arabic, but people look at each other and say hello here in the streets. In Canada, my next door neighbor never said hello to me in 15 years. Older people are treated with much more consideration here.

Tim: Do you have friends there?

Jearld: I have a number of gay friends and a few straight friends. I have a young man who works and lives here and helps me raise my parrots and and care for my botanical garden on the roof. I have up to 400 plants up there that take a few hours a day to care for. I also do my photography. The house is also a gallery of my work.

Tim: What kind of gay friends do you have there?

Jearld: Yesterday, a gay friend from Slovakia stayed here for a week. There are also websites and apps for meeting people.

Tim: How is the Moroccan government on gay stuff?

Jearld: Gay sexual activity is a criminal offense here. But there are thousands of gay-identified Moroccans. It's a very complex subject I could talk about for hours. There are definitely bars and cafés here that are considered gay. The most famous Moroccan gay person is a writer named Abdellah Taïa who lives in Paris and has written several novels about the gay experience in Morocco. I wouldn't exactly say that there is a gay community here, though. The whole thing with Islam and homosexuality—you have to back up and realize that the whole society here is based on gender separation. Men spend their time with men and boys and women with women and girls. Basically, that's it. So that's a form of homosexuality.

Tim: Or at least homosociality. But you're saying that the gender separation creates a kind of space for gay sex?

Jearld: There's a tremendous amount of gay sex. I've certainly had my share of it. But everything here is based on the family, and if the family finds out you're gay, that means you could be in serious trouble, so you have to keep a low profile.

Tim: What's a typical day like for you?

Jearld: I get up at 5am and enjoy a few quiet hours cooking or baking or looking after my cats and my parrots, reading the news online, doing a little writing, gradually going out and taking care of my plans. By 11am, I make my lunch. My young Moroccan helper has been here 12 years now but he doesn't cook. I'm a good cook and I enjoy it, and I learned a lot more during the pandemic. I'm 80 percent vegetarian. The fruits and vegetables here are absolutely wonderful. Then in the afternoon I do more plantwork. Lately I've been going to bed early, nine or ten o'clock. It's Ramadan now, so between six and eight p.m. it's iftar [the daily sunset fast-breaking meal] and people are all with their families. I'll usually watch a movie on YouTube or Netflix.

Tim: What do you love about living there?

Jearld: I've mentioned some of it—the climate, the produce, how people are toward me as an older man. Even the gay-identified Moroccans are much more interested in interacting with an older gay man than they would be if I were in Canada or the U.S. But there are bad things here, too. I'm actually hoping to move to the Philippines. That appears to be the gayest country I've ever encountered. People there are very relaxed about homosexuality, including the Muslims. As an older person there, I'm shocked by how much interest there is in me.

Tim: Is there a—transactional quality to that?

Jearld: Money? Usually not. It's the same everywhere when you get older. You just have to feel out every situation. In the Phillippines, most people I've met has been online. Never has there been any discussion of money, but sometimes when you can show—

Tim: I mean—do you feel implicated in sex tourism?

Jearld: I really despise the whole western way of looking at sex these days. Sex is a part of everyone's life. If you want to shut it out, okay, but— I'm not an aggressive person, and so if you meet someone in a gay website or app. Everyone's looking for the same thing. Take here in Morocco. If I go for a walk, chances are I'm going to meet someone. It's kind of like when I would go for a walk in Toronto in the 1970s. It was incredibly easy to meet someone.

Tim: Do you speak French?

Jearld: No.

Tim: So how do you communicate in Morocco with no French and only a little Arabic?

Jearld: The younger generation here speaks English. Unfortunately, their vocabulary and knowledge isn't very good.

Tim: Where do you want to live in the Phillippines—Manila?

Jearld: No, I would never live there. My final fantasy is that I want to build a real botanical or bird park…

I've been to Calauan [a municipality just south of Manila]. I need to spend a couple months there going to a lot of places. I went back to Mindanao three times and tried to get involved with a nature conservation called the Phillippine Eagle Foundation. That's a very threatened species that became their national bird in 1995. So I looked at some land just outside Davao City. They won't let foreigners buy land, which is partially understandable. I would leave whatever I develop to some conservation charity when I die. However, when I was meeting with the Eagle Foundation, I mentioned that I was gay and then the older man in the meeting didn't take that well and didn't follow up with me. It was kind of depressing.

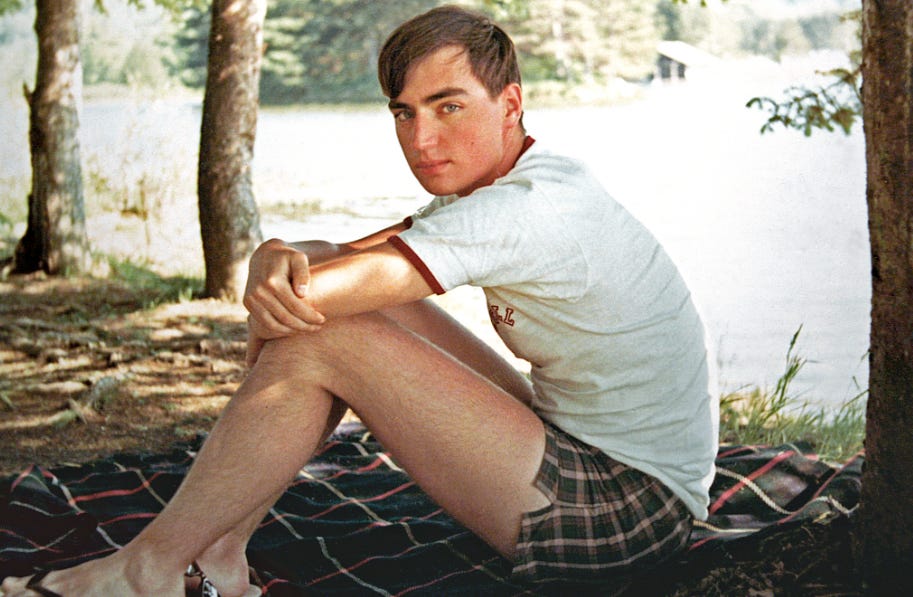

Tim: Okay. So let's go back in time now. So you are actually a U.S. citizen by birth—born in Niagara Falls in 1946, yes?

Jearld: Yes. I come from a lower-middle class background. My father had an eighth-grade education who became a self-made real-estate person. I had one older brother. My mother was a homemaker until my father died in 1970, then she went back to school. I was very eccentric as a kid. I was into insects and classical music and gardening.

Tim: When did you know you were gay?

Jearld: Probably by age 13 or 14. In high school, though, I had a girlfriend who was older than I was.

She was German and very aggressive toward me. I actually liked her brother. We almost got married; she moved to Ithaca when I went to Cornell on a scholarship. My parents never contributed a cent to my education; they didn't understand its importance.

Cornell was an exciting place at that time in the mid-late sixties. First, I dropped any interest or belief in religion at all. I was baptized in the Russian Orthodox church and went to a Lutheran church. At 14, my closest companion was a collie dog who was then hit by a car and killed. I went to the minister to see if the dog was in heaven and he said no.

By my sophomore year at Cornell, I was already in love with a boy whose parents were professors there. I was starting to loosen up a bit.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Caftan Chronicles to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.