Ian Levine was the 1980s DJ at Heaven, the Iconic London Gay Club, and Also Gave Us "So Many Men, So Little Time"

The British music obsessive and producer wasn't an easy interview. But he did have some spicy stories about pulling hot boys in white shorts off the dance floor and bringing them up into his DJ booth.

Happy January, Caftan readers! I hope you all had a good holiday break and are muddling through the winter okay, wherever you are. It's cold and dreary in NYC right now, but I actually like this time of year. With the commitments of the holidays behind, it's all about hunkering down to work, cooking warm cozy things (try this Thai-ish cod poached in coconut milk—I made it last night and it's amazing and so easy), hitting the gym to look presentable by spring and, um, what else? Oh yes—curling up with good books! I want to passionately recommend my longtime writer friend Mike Albo's brand-new novel Another Dimension of Us.

It's YA (young adult), but it's so funny, twisty and sweet—about nerdy and queer 1980s kids and queer/trans 2040s kids who all get sucked into the astral plane together, where they have to save one another from evil body-snatching entities called (lol) "Consumers." (A little late-stage capitalist critique there, Mikey?) It's truly sweet, slyly funny and ironic in a way that is sooo Mike, and the plot is bonkers, like the best season of Stranger Things meets A Wrinkle in Time meets The Breakfast Club meets Euphoria. I'm not kidding!

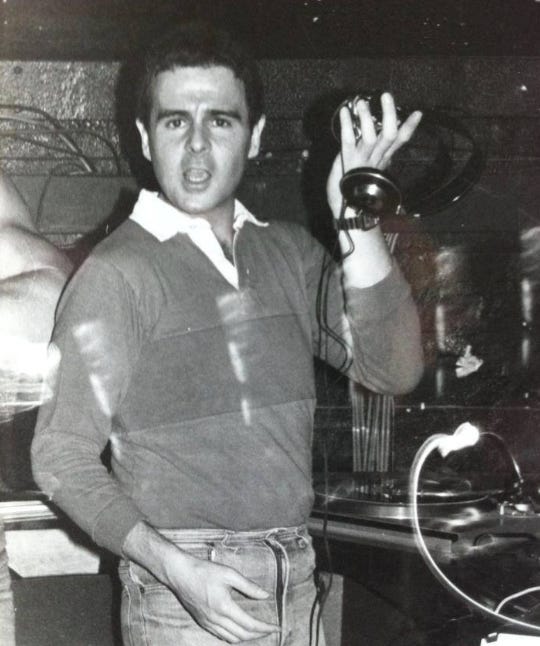

This month's interview is with Ian Levine, 69, of London. Maybe you haven't heard of him, especially if you're American, but perhaps you've heard of Heaven, the legendary London gay club (Andrew Hollinghurst brings it to life vividly in The Swimming Pool Library, one of my favorite novels). Ian was the main DJ there through the entire eighties, pioneering the style of 1980s gay post-disco club music—which we associate often with The Pet Shop Boys, Bronski Beat and Erasure— that came to be called Hi-NRG. He wrote and produced the super-gay Hi-NRG hits "So Many Men, So Little Time," with its deliciously early-eighties-gay video full of actual gay men from Los Angeles...

...and "High Energy"...

And he also went on to remix and/or produce a string of UK pop sensations like The Pet Shop Boys, Bananarama, Erasure, Bronski Beat, Tiffany, Take That and Boyzone. He's done quite a bit else, like some truly amazing genealogy work reuniting his own clan, which was traumatized and broken up by the Holocaust, and is also perhaps the world's biggest and most influential Dr. Who fan.

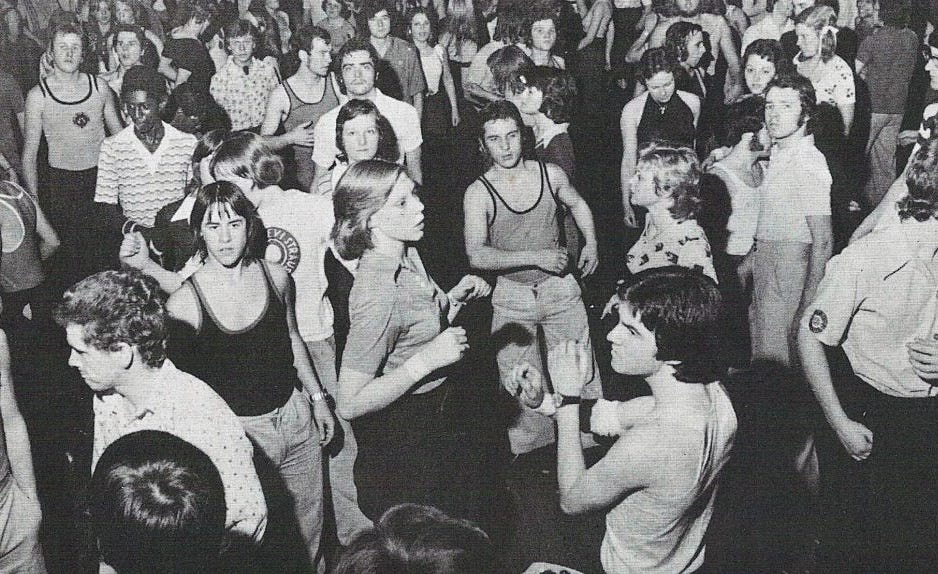

Even before Ian was at Heaven in the 1980s, he learned to DJ as part of the early-70s British Northern Soul scene—a milieu I've always been obsessed with, in which working-class mainly straight kids in the industrial north of England would get high off their face on speed and dance in huge clubs to sped-up obscure sub-Motown 1960s American soul records. (I've always thought it would make an amazing movie.)

So when someone suggested I reach out to Ian to interview him, I knew we'd have some shared passions, as I used to DJ myself and am a huge history of every single phase of dance-music and DJ history—especially the gay aspects. Ian, who suffered a stroke a while back and now needs a lot of help in his daily life, was gracious to accept my interview request and give me the time, but I'll be honest—it was a very tough interview. He talked over nearly all of my questions and, especially toward the end of the interview, devolved into basically ignoring me completely and DJ'ing at me whatever song popped into his mind. We really start to fall apart toward the end and talk about why he might have such a hard time having a true back-and-forth with another person. It might have been the first time I, and not the interviewee, ended a Caftan interview, at about the 90-minute mark. And I did so because I had not a drop of energy left in me to try to have a real conversation with him.

Still, I'm grateful he agreed to do it, as I'm grateful to every one of my Caftan interviewees regardless of how good the interview is. There's definitely lots of good stuff in here—just don't expect a lot of introspection or staying on any one idea for too long. I think next month's interview will be richer—it's with a true legend of the NYC gay publishing/literary world on the release of his own latest memoir, which I am very excited to read shortly. Meanwhile, I am happy to give you Ian Levine, who asked that I include his podcast Solid Soul Sensations, in which he plays a lot of old rare Northern Soul tracks.

Caftaners, please drop me a line if ever you can think of a gay man age 60 or older who's led a notable life—I can't promise I'll pursue, as I have my own quirky ideas about who seems or seems not to be a good interview, but I'll definitely consider! And I know I always say this, but—I'm really grateful for the support, especially the paid support. These interviews take a lot of time, and the bit of income I get from them allows me to do them without losing too much income taking time away from other assignments.

So here's Ian!

Tim: Hi Ian, thank you so much for agreeing to chat with The Caftan Chronicles.

Ian: [calling to someone] Can you turn the rock music off? I'm doing an interview. [to me] That's Aidy, my assistant who looks after me.

Tim: Oh, okay. So you said you live in West London, in Acton. Can you describe your house?

Ian: It's two huge three-story houses knocked together. It's got 25 rooms, a lot of which are storage for my records and equipment. The housekeeper's daughter lives here and Aidy lives here part time. I had a stroke nine years ago that completely disabled me. I live in about four or five rooms. They all house my master tapes and recordings and records. I have 150,000 vinyl singles. I've got 2,000 tapes I've recorded over the years. I have four white Eskimo sled dogs—Colombo, Madison, Myla and Bobby—and a white cat named Tamla, like Berry Gordy's label that merged into Motown in 1960. I actually don't own this house anymore, I sold it, but I have the right to live in it until the day I die.

Tim: Okay, cool. What is a typical day for you like?

Ian: I don't ever wake up before 10am. Someone has to dress me because I can't use my left hand or left leg. I spend most of the day on my computer. We put a lot of records out on vinyl. We have a studio set up here in the house.

Tim: Where you—remix tracks?

Ian: Remixing is the wrong word. I'll call it de-mixing. We try to make things sound more sixties and less modern. All the 80s and 90s shitty electronic drums, which I hate, we replace with real drum sounds. My most successful tracks ever were "So Many Men, So Little Time" and "High Energy." But my taste is soul music, not disco remixes. I remixed half the hits of the 80s—the Pet Shop Boys, Bananarama, Erasure, Bronski Beat, Tiffany. But after that I got back into Northern Soul again. My fans who love disco don't understand, but I cringe when I listen to a lot of disco and dance music.

Tim: Really? Why?

Ian: Because it's too gay. It's pigeon-holed. I prefer Motown—beautiful, uptempo, joyous melodies and chords, proper three-minute songs. The disco and dance stuff I used to remix had a three-minute intro before you even heard the singer. I did that for the Heaven dance floor. The kind of disco I love is glorious, romantic, string-filled disco, like Phyllis Nelson's "Don't Stop the Train."

Tim: Okay. So you are in front of your computer all day...

Ian: Going out of the house is murder. I have to get down the stairs, which is painful and an effort. I don't go out much anymore. I had 70 people come for my last birthday party. I got out about twice a week for doctor appointments. My health has been shit—stroke, bladder cancer, then sepsis, sarcoidoisis. I'm still trying to do as much as I can while I'm still here. I did a lot of genealogy work and traced my family so far that I found out it contains Barbra Streisand, Billy Crystal, Amy Winehouse and Steven Spielberg. On ancestry.com, you have DNA matching and through-lines where you can match your ancestors to other people's.

I used to love fine dining at the London restaurants of Marco Pierre White, one of the world's greatest chefs. I used to see Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman and Princess Margaret at his restaurants. But now I've taught Aidy how to cook. Today we had grilled seabass with whipped cream potatoes. New Year's Eve, we even went out to dinner. My gay cousin Julian's husband is the manager of Min Jiang on the tenth floor of the Royal Garden Hotel in Kensington. I have to go out in a wheelchair.

Tim: Well, I'm glad you had a nice New Year's Eve dinner. So you were born in 1953 in Blackpool, which is on the coast of the UK facing toward Ireland.

What were you like as a kid?

Ian: A bit of a genius. When I was seven, my teacher was lecturing on dinosaurs and I told her she got it all wrong and she had me lecture the class instead. I was also in a talent contest where I sang "Wouldn't It be Loverly" from My Fair Lady.

Tim: Yes, and you become a music fanatic at a fairly early age. Can you talk about that?

Ian: It was Motown. I was 13 and the radio in England played bland pop like Cliff Richard...

...but Radio Caroline {founded in 1964) played Motown—the Supremes, the Four Tops, Martha and the Vandellas, the Marvelettes, the Velvelettes—I fell in love with it.

Tim: Why? I should say I love Motown too. But why for you?

Ian: That beat! The fact that the lyrics could be like "My world is so empty without you," but the music was so happy and fast. The Four Tops, "Since You've Been Gone"—the vibraphone hits you with the beat and the bass line is the predecessor of disco and Hi-NRG. I had dinner with [Motown hit writer] Lamont Dozier [who just died last summer] once and he said, "I took a rock and roll beat and mixed it with jazz chords, and that was the Motown sound." They took very sophiticated chords, ninths and augmented thirteenths, and put them into a straightforward four-four beat and made them the sound of the Baby Boom Generation.

Tim: Why do you think on a personal level you were so drawn to Motown?

Ian: I don't know—I'm not a psychiatrist. So I was DJ'ing at Blackpool Mecca by the time I was 17, in 1970. We were playing Motown-type records that were already five or six years old, by obscure artists. Like Robert Knight's "Love on a Mountaintop"...

...and it was reissued and went to #2 on the UK pop charts. So this scene became known as Northern Soul—all the clubs in the north of England playing Motown-era tracks after America left them behind. But I would also spend a lot of time in the U.S., where my parents had an apartment in Miami Beach, and I would go to record shops there.

So I started looking for the Motown sound on other labels and that's how I discovered The Impressions [out of which came Curtis Mayfield] and The Masqueraders. For me, it became all about finding records nobody else could find.

Tim: I am so fascinated by the Northern Soul scene, which the British author Bill Brewster writes about so vividly in his incredible 1999 dance music/DJ history book Last Night a DJ Saved My Life.

How would you explain Northern Soul to someone who hasn't heard of it?

Ian: it's the 1960s Motown sound but done by labels other than Motown [like Chess and Stax].

Tim: Right, and it was early 1970s working-class Northern UK kids in a very bleak industrial part of the country breaking into pharmacies and stealing all the speed and getting fucked up and going to these warehouses where they would dance off the walls to sped-up versions of this obscure 1960s American soul.

A true example of cultural hybridism. But that scene was not very gay, was it?

Ian: The DJ Les Cokell was gay. But no, it was a very straight, macho scene.

Tim: When did you first realize you were gay or had gay feelings?

Ian: I tried to suppress it until I was 25. I was in New York City in 1975 and [dance music pioneer] Tom Moulton, who became a great idol of mine, took me to the new gay club Infinity and it was a life-changer.

Infinity is what we modeled Heaven after—a long, rectangular club with the DJ booth in the middle, high up on one side overlooking the dance floor, big raised black felt banquettes, dancers with silver and gold fans, no shirts. Cerrone's "Give Me Love" with the break near the end where the beat stops and the strings carry on…

…and the whole crowd screaming their tits off, waving fans. It was a magical moment that affected me for the next few years. A few years later I produced the track "My Claim to Fame" by James Wells, which was inspired by Cerrone. It's an absolute disco anthem. Nerds think of disco as The Bee Gees and Donna Summer, but people who are really in-the-know know James Wells.