Food Bar and G Lounge Were The Places to Be in 1990s-2000s Gay Gotham. Pat Rogers Made Them Happen.

Now living in Hollywood, the former entrepreneur talks about the rough-and-tumble world of running a venue in late 20th century NYC, and about the joys of sex at 79.

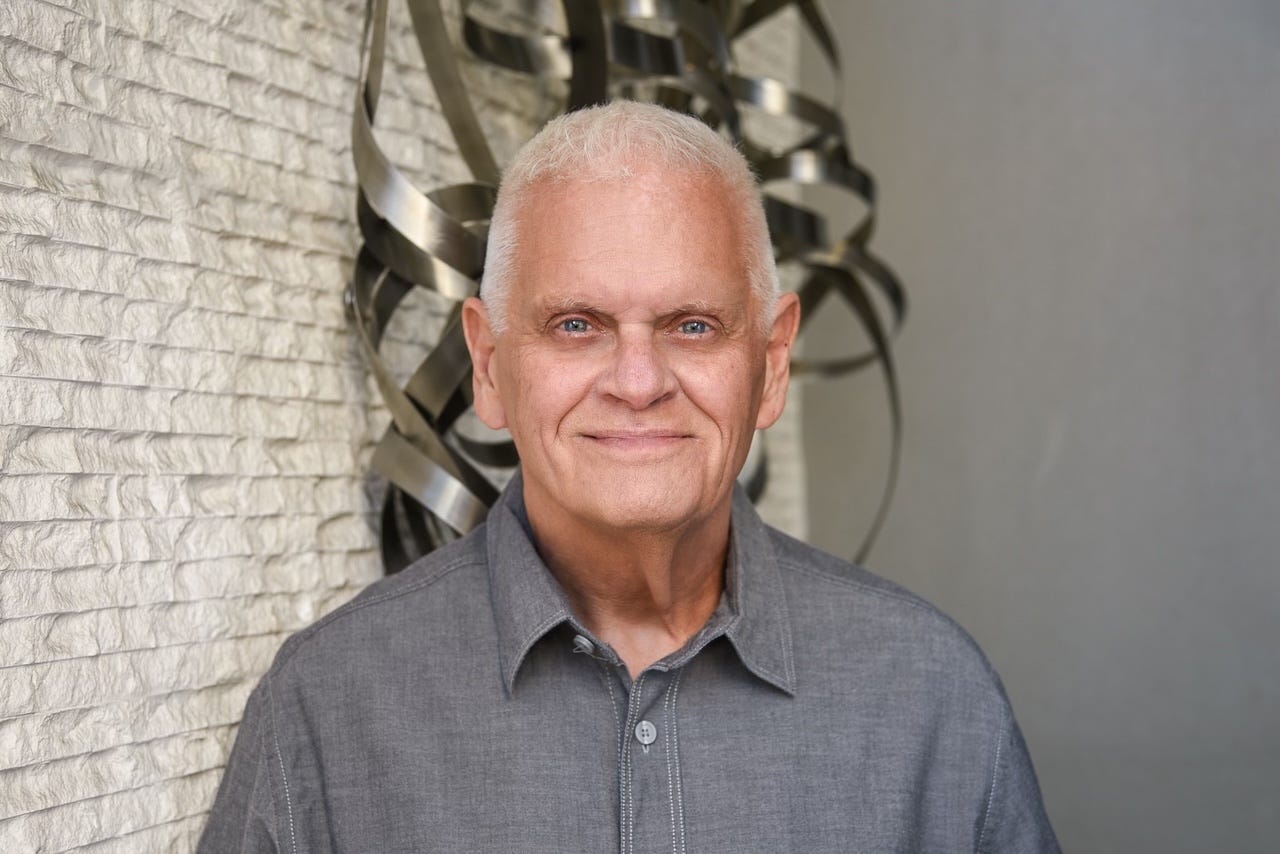

Happy holiday season, Caftan readers! Thank you once again for supporting this project of having long talks with older gay men about our amazing lives. I had a huge increase in both free and paid followers in 2022, Caftan’s first full year, and I’m super-grateful. I’m still at that point where, for every interview you read, there’s probably been 5-6 guys whom I didn’t hear back from, or who declined, or who backed out at the last minute, which is frustrating AF, especially when they’re non-white voices I’ve been trying really hard to get. But then I finally do an interview with someone like Pat Rogers, 79, who lives now in L.A. but once co-owned the gay NYC institutions Food Bar and G Lounge—and all the hustling seems worth it because the conversation is so good.

And this is a good one. If you lived in—or even just visited—NYC in the 1990s and 2000s, you probably went, even at least once, to Food Bar and/or G Lounge, which were two of the defining venues of Chelsea at its gay-clone heyday before the clones migrated northward to Hell’s Kitchen, or, for the more “alt” ones, southward to Williamsburg, Greenpoint or Bushwick in Brooklyn.

I’ll totally admit that seeking out an oral history of these places was pure nostalgic indulgence on my part. I can’t even count how many lunches and dinners I had at Food Bar when I was in my twenties and early thirties, and I’m particularly nostalgic about G Lounge because, throughout 1999, I DJ’d the early shift (6-9pm) on Thursdays, starting chill and eclectic with, say, Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” then merging into Chaka Khan’s “Chanson Papillon,” then ramping it up—per my mandate from our DJ den mother, Brenda Black—so that by 9pm, the space was bumping to the latest house tracks, like “He is the Joy” and “Music Sounds Better With You.” Good times—accompanied by too many comped frozen cosmos and maybe a few other things too. Ahem!

Pat was an easy-going delight to talk to. He didn’t have a super-granular memory of things I’m obsessed with, like what people were wearing at the time, what music they played in the restaurant or bar, what food they served. He’s always been more about the business rather than the creative side of his ventures, and I found that perspective interesting. God knows I’d probably never have lasted as long as he did running businesses in tough-as-nails NYC.

Also, as you’ll soon learn, he’s not much for reflecting on his past. But this interview still worked for me, especially when Pat discusses, with total enthusiasm and detail, his thriving sex life at nearly 80, including his highly successful penile implant. A conversation like that is hitting my personal bull’s-eye of what a good Caftan interview is. It’s about how we go on fulfilling all the levels of life—professional, social, romantic, sexual and spiritual—as we move past 60. As someone who’s 53, I feel like with each Caftan interview I do, I get a little wiser about how to make choices in the years ahead—and I love that. The interviews also make me feel like I’m a link on a chain of gay male lived experience that gets passed from one generation to the next, and I love that, too.

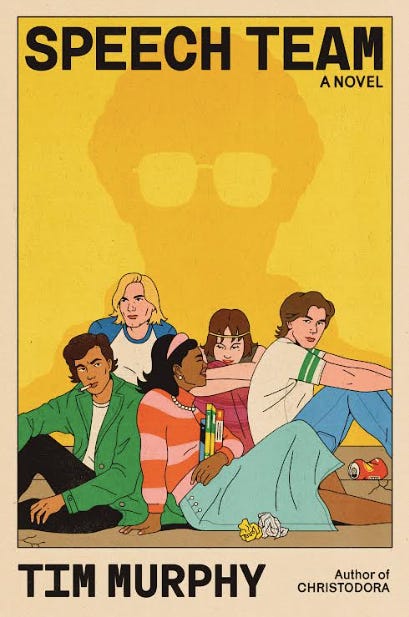

Oh, hey! Before we begin the interview, check out the cover for “Speech Team,” my fifth novel coming out in July…

I’m super happy with it. I asked them to riff on the poster for “The Breakfast Club,” but with something more ominous in play, and I think they (or I should say the talented illustrator, Nada Hayek, my fellow Lebanese-American) nailed it.

I wish you all the very best holiday season and New Year. I’m working on lining up my 2023 Caftans already, so please drop a line if you have ideas, or just to say hello and what you like or don’t like about the series so far. I’ll reiterate my gratitude to all of you. I have to pinch myself a little that what, more than a year ago, was just an idea I wondered if I could pull off now has over 1,000 followers. Please tell folks about it and help me expand the list.

And with that, I give you Pat Rogers! (I also want to thank Brandon Voss, who curates the great Instagram account of old HX covers, for some of the photos, especially because it doesn’t seem like there’s many old photos of Rogers & Barbero and Food Bar out there, sadly. It was the pre-iPhone era, where, if you wanted to capture an evening, you actually had to bring a damn camera!)

Tim

Tim: Pat, thank you so much for agreeing to talk to The Caftan Chronicles about your iconic 80s, 90s and 00s gay NYC restaurants and bars. So may I start by being so bold as to ask your age?

Pat: I'm 79. I'll be 80 the day after Christmas. I've still got good energy and I stay active. I have a master's degree in theater, so I'm trying to get with some of the local theaters here like Geffen and the Pasadena Playhouse to do volunteer work. I live in Hollywood, on the top floor of a high-rise on La Brea and Franklin, with my dog, Miku, a Shiba Inu who is the love of my life.

Tim: Wonderful. Can you tell us about your childhood?

Pat: I was born in 1942 in Wichita Falls, Texas. I was a pretty blond child, very sheltered. My dad was a local distributor for Frito-Lay overseeing 22 counties in Oklahoma and Texas. He was a very hard worker who taught me all about hard work, and it rubbed off. I grew up in a neighborhood with about 10 other boys my age, but I wasn't allowed to go out that much because I was supposed to stay home and practice piano. When I was very young, my grandmother took my sister and me to a drive-in to see "Mr. Belvedere Rings the Bell" with Clifton Webb, and at the end they played the chimes, “The Church’s One Foundation”…

…and I went back to my grandmother's house and picked out the tune on the piano and they thought I was a genius, so I was forced to take lessons and I hated every minute of it. I was a rebellious kid.

Tim: When did you know you were gay?

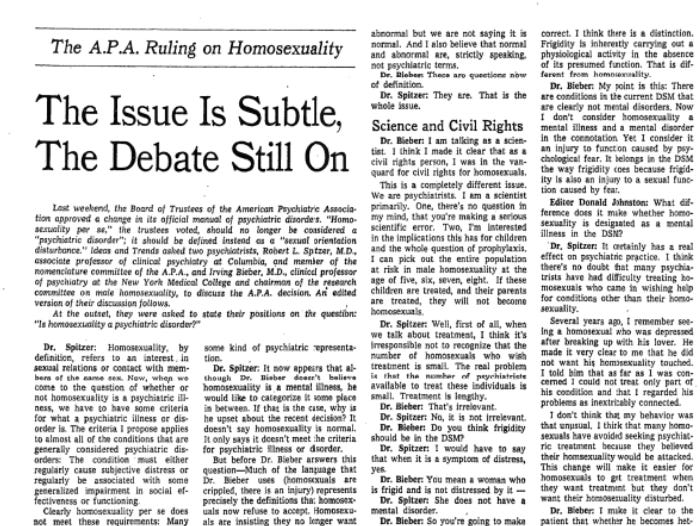

Pat: I didn't admit it until my mid- to late-thirties, but I knew all along I was gay. I spent 20 to 30 years trying to cure myself. The American Psychiatric Association listed it as a disorder until 1973.

But even after they delisted it, my shrink tried to get me to realize that I wasn't gay, and it just wasn't working.

But anyway, backing up, I went to Texas Tech and started out in architecture but hated it once I realized I had to take physics, so I switched to theater and my parents were horrified. Once I told them I was taking theater in order to be a teacher, they were a little more accepting. This was early in the Vietnam War, which I wasn't for or against, but I could see that the U.S. was not really trying to win it but using U.S. soldiers as fodder to maintain some sort of position. I thought, "I'm not getting involved with that."

Then I received my draft notice and thought, "Oh, God." At the time, I'd been working with the Santa Fe Opera for two summers backstage. So I ended up going into the Peace Corps as my only option to avoid military service. So I went to India for two years, to a small village in Maharashtra called Buti Ori. It was frightening at first. Then I thought, "Well, I'm halfway around the world—I might as well learn something." I've always been a glass-half-full person. We were assigned to work at the local agricultural school.

Then I came back to college in Texas and also got my theater master's. After that, I didn't know what to do, so one Christmas holiday in 1971, I went to New York and fell in love with it.

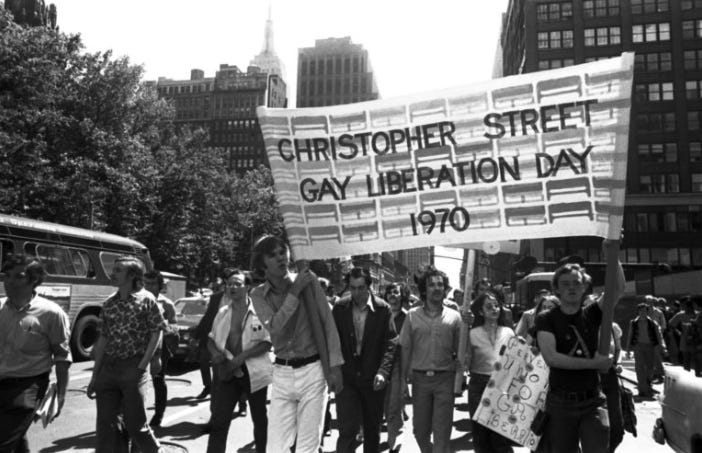

It was a little intimidating but it had an energy that matched mine and I was ready for the challenge. The Vill-ahge was where all the gay scene was.

I lived on the same block as [NYC's oldest gay bar] Julius' [which the city just landmarked]. Four of us, all gay, were living in a one-bedroom apartment. One of them I'd met when I'd visited the city the previous Christmas and fallen in love with him—or so I thought. He was just a puta, a real whore, which today I admire, but at the time I was very sexually strict. Anyway, we moved in together when I was down to my last $30. I had a temp job Xeroxing eight hours a day. I can't tell you how numbing it was, so when the manager offered me the actual job, I thought, "I'll kill myself if I take this job," and I turned it down.

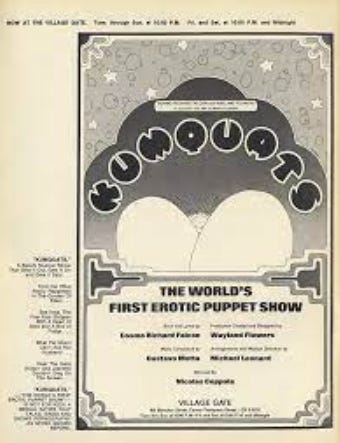

So then I got a job backstage with "Kumquats," which billed itself the world's first erotic puppet show, in the basement of the Village Gate.

That was where Wayland Flowers was the lead puppeteer, and where Madame first appeared in public.

It was a musical review with a lot of blackouts. One number, which looked like a furry cunt, was a take-off on Ethel Merman. I was the assistant stage manager. It didn't last long. I also did some stuff at [the theater] La Mama and tried to sleep with as many people from "Jesus Christ Superstar" [which debuted on Broadway in 1971], thinking maybe I could get a job on the show. It never happened.

Anyway, this was all still part of the hippie period—1971, 1972.

Tim: I'm curious to know what restaurants and bars you went to at that time, given your future career.

Pat: Phebe's on East 4th St. was pretty gay.

Tim: Really, it was? I went there a lot in the early 90s when I first moved to NYC and I don't remember it feeling gay. It felt very post-collegiate fratty.

Pat: Well, that was the main place, but I didn't hang out a lot. I'd met this Jewish guy who was a bartender at the Village Gate who I thought was beautiful. I even put on some makeup to attract him, and during the "Kumquats" intermission he came into the lighting booth and started chatting with me, and after that, we were thick as thieves for almost a year.

Tim: Wow.

Pat: But I gave myself up to him. That's always a mistake for any young person in their first affair, and it made me less interesting to him. He introduced me to his therapist, who actually was in Easton, Pennsylvania and did a kind of therapy called orgonomy, based on the writings of Wilhelm Reich, one of Freud's assistants. He created the Orgone box, an energy box that that is supposed to drain bad energy from you.

The first two or three sessions with him, he'd make you strip to your underwear and socks. I asked why, and he said that he needed to look at my muscles. Then he'd ask me to breathe deep or kick. He manipulated my jaw. The purpose was to evoke emotion, and it always worked because I would cry.

This therapist knew I was into guys, obviously, because my boyfriend was his patient. I tried to abstain from gay sex. Oh, my God—I was willing to.

Tim: So some part of you didn't want to be gay, despite being in the post-Stonewall Gay Pride milieu of the Village?

Pat: Well, I didn't go to therapy because I was gay—but because my boyfriend would not sleep with me one night and it flipped me out. But I ended up being with that same therapist for 30 years. At some point, he realized that the APA had delisted homosexuality as a disorder.

Tim: So you saw him until you moved to L.A. around 9/11, yes?

Pat: Yes. I've often said I went to therapy to get a Ph.D. in me, and to be more capable of doing things. But then I had to ask myself, "Well, if that's the case, Blanche, why aren't you?" But therapy did make me more aware of myself and of people around me. It was eye-opening, and I needed it. I'm somewhat aggressive. Maybe very aggressive. And I get tired of things, so I have to move on. And that can be good or bad. I've managed to keep my businesses open as long as I've wanted them. But I've never felt that I was a success.

Tim: Why not?

Pat: In my opinion, each time, I never got out of my businesses in the best way. For instance, when we sold Food Bar to Joe [Fontecchio], we'd already converted it to Che 2020, which was stupid.

Tim: Okay, we'll get there. But let's get back to your path in the early 1970s.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Caftan Chronicles to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.