"Emerald City TV" Is a Stunning Time Machine Back to 1970s NYC Gay Life

I chatted with Steven Bie, the surviving producer of the weekly cable show that depicted disco-era queer culture in all its exuberance, raunch...and innocence.

Hey there, Caftan readers. I hope this finds you all well as we head into spring amid what seems unrelentingly dark times in the world. I'll admit that my enjoyment of a recent spate of very balmy New York City days has been shadowed by the constant thought of what is going on in Ukraine, and what it might mean for that whole region and the world in the months and years ahead. (Here is a link, via Congresswoman AOC, where you can donate to vetted groups addressing the Ukrainian refugee humanitarian crisis. I just did.)

Meanwhile, one can always look back, which I guess is the whole point of The Caftan Chronicles. I've put a lot of time recently into lining up future interviews, and I am very excited about a certain gay literary lion I have lined up for the June interview. This month, however, I will deviate slightly from my usual all-Q&A-all-the-time format to rave about something that, to my great shock, I only just stumbled upon online a few weeks ago. It's Emerald City TV (this links to all the episodes available online), which was a weekly gay newsmagazine that ran on Manhattan's cable station "J" from late 1976 to 1978.

Only a few years ago, Steven Bie, the only surviving producer of the show—the other two were Frank O'Dowd, who died of AIDS in 1988, and Gene Stavis, who died in 2014 at age 70—put onto YouTube the series archive, whose official home is the LGBT Community Center archives, where the footage awaits being restored.

Perhaps the show's only recent appearance on YouTube is why I hadn't previously heard of it. But I'm still shocked, because I've been forever obsessed with gay ephemera and vintage anything. I'm that gay that, in my twenties in the 1990s, would buy armloads of the 1970s gay New York nightlife magazine After Dark whenever I found them at the old Chelsea flea markets.

I've often said that my idea birthday present would be to go back in time to a weekend in NYC in the 1970s—my only problem would be picking exactly which year, and what my itinerary for the night would be. Burgers at David's Pot Belly on Christopher Street followed by catching Edie Beale at Reno Sweeney's, then dancing the night away at Flamingo followed by a raunchy trip to the Anvil? My mind spins at the possibilities.

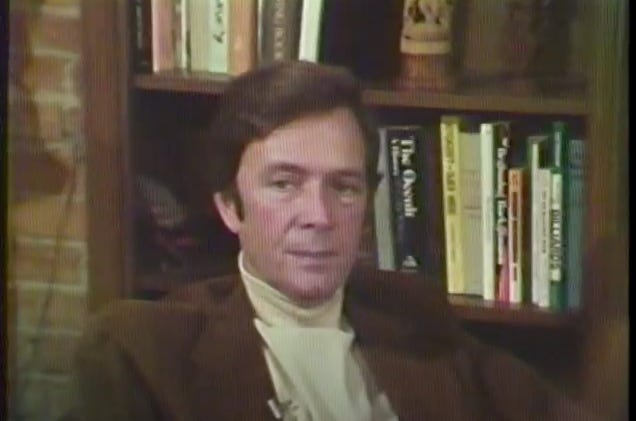

Absent a time-travel machine, though, stumbling upon Emerald City TV was the next best thing. The luminaries that the show managed to get interviews with boggles the mind: The very WASPy James Kirkwood (the novelist who also wrote the book for A Chorus Line)…

The gay historian Jonathan Ned Katz. A very young John Waters being interviewed by Vito Russo, who often did film-related chats for the show…

Quentin Crisp. The owners of the bathhouses Man's Country (which actually replicated on one of its many floors a giant truck like the ones down by the piers that gay men would have sex in) and the East Side Baths. Butterfly McQueen—alongside footage of her appearing at the venerable 1970s Village cabaret haunt Reno Sweeney…

(If you ask me, her interview is a cringe-y example of a Black celeb at that time restraining themselves from saying what they really want to say—particularly about her demeaning role in the racist blockbuster Gone With the Wind.)

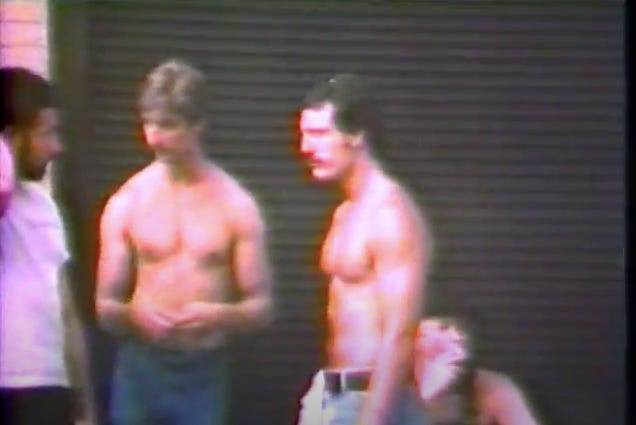

But the makers of ECTV would also take their unwieldy early-video equipment out of the studio and shoot on location on Fire Island...

…right inside clubs like Reno Sweeney or Village gay theater shows like "Boy Meets Boy"...

…at the 1977 and 1978 Pride marches…

…and subsequent celebrations in Central Park, with performers like Patti Smith.

It's stunning. You can almost pretend you're there among them, drinking beers and smoking joints and wearing a tight Lacoste shirt, soft-wash flare jeans and early Nikes—or perhaps with a tight flannel shirt unbuttoned halfway down your chest, chiseled in that muscular-but-lean 1970s fashion.

Borough-specific variations of that good old-fashioned Noo Yawk accent abound, so reminiscent of a time when the city was still made up of more natives and Long Island and Jersey types than it seems to be today.

As Steven Bie, 66, said in our chat (below), "New York felt like a smaller town then, where everyone eventually knew everyone else." Perhaps that was because there was no Internet, no social media. The world was smaller. The people you knew were the people you saw when you actually left the house, and on an island as small as Manhattan, in a community as ghettoized as the downtown gay world at that time, you really could come to feel like you knew everyone after a few years.

What's most thrilling to me about ECTV is watching a community, not even a decade after the Stonewall uprising, come into its self-confidence and its cultural power—this self-conscious sense that to be gay was to be cool, to be free, to be part of the zeitgeist.

And also to be political. As Katz says on the show of his own coming out, it was a process of transforming his own self-image "from a psychological freak to a member of an oppressed minority group." I've always heard how the Florida antigay initiatives of "Orange Juice queen" Anita Bryant galvanized the U.S. gay community into its biggest surge of pre-AIDS activism…

…but ECTV really drives it home. Bryant is a bogeywoman who comes up again and again in the 1977 episodes, the butt of jokes and impersonations that actually feel gentle by today's brutal meme-driven standards. (Except, perhaps, for the posters of her effigy alongside Hitler's at the Pride march.)

Also, can we just talk about the commercials, most of which are for gay or gay-leaning restaurants (Jan Wallman's!), bars (Ice Palace 57)…

…bathhouses (the Man's Country ad is super-sexy)…

…magazines and answering services. (My single favorite line from Sondheim's 1970 Company may well be "Look, I'll call you in the morning, or my service will explain.")

As Bie told me, the ECTV producers usually shot their own commercials for advertisers. That means we are actually in the bars and clubs—or, in yet another fascinating discovery for me, at the all-gay Catskills residential community of Roxbury Run Village (which appears to still exist, its oh, so chic 1970s architecture intact, even if it's no longer gay)…

"If you like the island," says the ad, referencing Fire Island, "you'll love the Village"—alongside shots of hot, often shirtless men swimming, playing tennis and riding horses.

Gay life as depicted by ECTV is shockingly male and white by today's standards. There are a few intrepid female (presumably lesbian) interviewers and correspondents, and of course there are the beloved divas and female allies of the period like Bella Abzug…

…but in ECTV's vast buffet of men as sex objects via ads and magazines, men of color are almost never depicted, except for a moment in the show's fascinating opening sequence (featuring gay slices of life all over the city, backed by Ella Fitzgerald's all-too-sedate 1950s version of "Anything Goes") showing two shirtless Black men dancing a kind of hustle together.

And you only have to look at the racial diversity of footage from, say, the Central Park Pride be-ins to know that this was not a matter of the diversity not being available, but of magazines like Blue Boy and Mandate almost never featuring it. There’s one moment that’s very telling—the host, Frank O’Dowd, is introducing the first show after what was apparently a very rainy summer of 1978, and he says that everyone going into the autumn is “a little more Caucasian than usual…we can all look forward to another seven or eight months of milky white complexions…so let’s put away our Lacoste shirts and take out those bomber jackets.”

I holed up with ECTV episodes several nights in a row last week. Of the many fascinating interviews, I found most fascinating the 1978 one with a (hot fortysomething) Larry Kramer talking about his new, explosive, thinly-veiled Fire Island sexual tell-all Faggots.

It's absolutely haunting: Here is Kramer, at the height of the gay sexual revolution and at least three years before more than a handful of people understood that a health crisis was brewing, lacerating his fellow gay men for their sexual wildness and saying that homophobia is basically their own fault for retreating into ghettoes and centering their lives around sex instead of fighting 24-7 for full rights and societal inclusion.

"We've done everything to ourselves," he says. "Stop making excuses and look at yourselves. You have to like yourself...Why do we fuck in the bushes at night? ...We don't have any responsibilities [like raising kids] ...I think ghettoes are a dead-end for any group—gays, Jews, Blacks....I don't see what fucking in the back room of the Anvil gets you...People can't wake up at 60 and say, 'Oh, poor me' [for having no other life]...You got what you deserve...How can you feel good about yourself as a person after you've been pissed on in a bathtub?"

I definitely want that last line on a T-shirt. But seriously—I had such violently mixed feelings about Larry's words here (whose harshness is tempered somewhat by his own admitting that even he can't seem to sustain a long-term relationship). On one hand, could he not appreciate the celebration, the joy, the liberation and ecstasy that was gay life in 1978 NYC? AIDS probably made him feel grimly vindicated!, I thought bitterly.

And yet at the same time—it's hard not to love him for wanting more for his people, for wanting our full personhood within society. The Village and Fire Island in the 1970s sound like enchanted places I'd time-travel back to (temporarily) in a minute, but in 1978, they were among precious few places where gay men could be themselves without fear of violence, firing or other repercussions. They weren't "real," in many senses of the word. And it's heartbreaking that it took the plague of the 1980s and 1990s to all but force society to reckon with gay personhood—a bitter bridge that brings us to where we are today.

As I watched episodes of ECTV, I took to Googling everyone I "met" to see who was still alive. Precious few, in fact. The vast majority died of AIDS about a decade later—including O'Dowd, the show's adorable, slyly flirty dark-haired host, who passed in 1988 after being involved in ACT UP.

To watch so much sass and life, amid an era of liberation and cultural flowering, and to know that so many would be dead in a decade, usually before the age of 50 (often 40), was haunting, heartbreaking. And yet I still marvel at this time capsule that I did not even know existed—this precious compendium chronicling just a few magical, sexy, campy—and, as Steven says himself below, somewhat cornily innocent years, even if some people were getting fisted and pissed on. As much as today's Gen Zs seem obsessed with so much of the pop culture and iconography of the '90s, young queer culture in the 70s was equally fascinated with the vaudeville and Hollywood icons of the 1930s and 1940s. Elements of that show up in almost every bit of drag theater featured on ECTV, highly reminiscent of Bette Midler's "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy" revivalism of her fledgling "bathhouse Bette" days of the early 1970s.

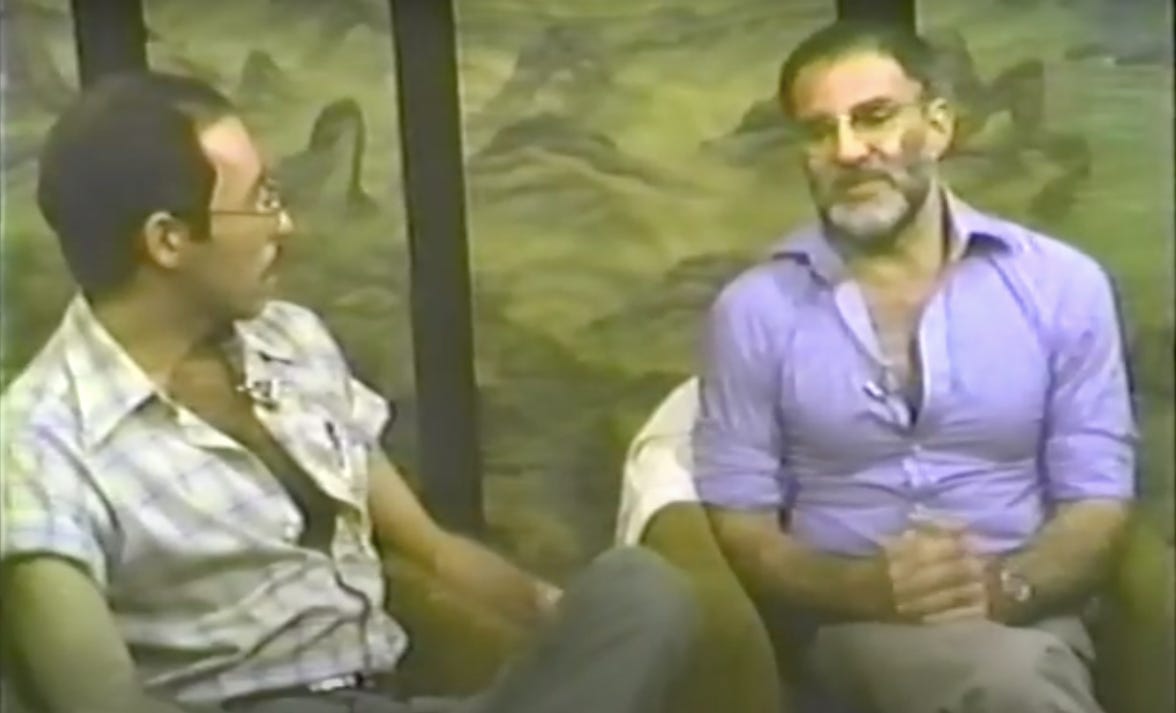

I am grateful to Brandon Judell, an occasional interviewer on ECTV…

…who is still a theater and speech professor at CUNY, who chatted with me briefly and connected me to Steven Bie (who doesn’t like to be photographed), who still lives on Christopher St. and is retired from a long career working at high-end NYC hotels like the Pierre, the St. Regis and the Plaza Athénée.

Our chat follows...

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Caftan Chronicles to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.