Daddies, "Cruising," "Making Love," "All About Eve," "Mommie Dearest": The Best Talk With Film Geek Mark Harris

The longtime Entertainment Weekly editor, author of juicy books about American movies and husband of Angels in America playwright Tony Kushner on our favorite men and women on the screen.

Caftaners, what a week this has been. (I write this the weekend after the election.) Amid our freakish NYC Frankenweather, summer days in November and brush fires in the parks from a lack of rain, I’ve felt a profound darkness, a sense of gathering shadows, around me since Tuesday night, as well as the maddening state of living in uncertainty (we won’t really know what happens until next year starts to unfold) and also, thankfully, gratitude and tenderness toward my friends and my gay community, who make present-day life bearable, along with dancing and movies and the gym and cooking and going out for a drink and a few other things. May we be able to hold onto those things, especially the friends and the ability to convene with them.

I wasn’t so much shocked or outraged by this week’s results, as I was (along with so many others) in 2016. This feels more like a period of chastened, sober quiet, trying to figure out what Trump voters want and if they can have some of those things without hurting or scapegoating others, and if Trumpworld and Project 2025 world have a darker and crueler and more repressive vision for this country, and the world, than what his voters signed up for. It is all so very, very much up in the air, leaving also in equipoise the clashing instincts to take a breath, wait and see, hope that the darkest attempts will be thwarted or kneecapped, as may of them were during Trump 1.0, or to see the fucking writing on the wall, to see the runway cleared for extremism in a way it wasn’t eight years ago, and get the hell out here, whatever that means. What “resistance” means this time around, and how to know what advances are most important to resist—because we likely can’t resist them all, whack-a-mole style—also feels in suspension.

As I write this, it occurs to me that some of you readers might have voted for Trump. How would I know? After this election, increasingly it occurs to me that not everyone around me, even in the largely liberal parts of NYC where I live and hang out, may feel the same way I do. (You probably know that Trump’s numbers went up, albeit modestly, in many parts of NYC this time.) I’ll just end by saying that, whatever comes next, my hope is that as few people as possible are hurt, and I’ll try to do my part around that as the picture becomes clearer.

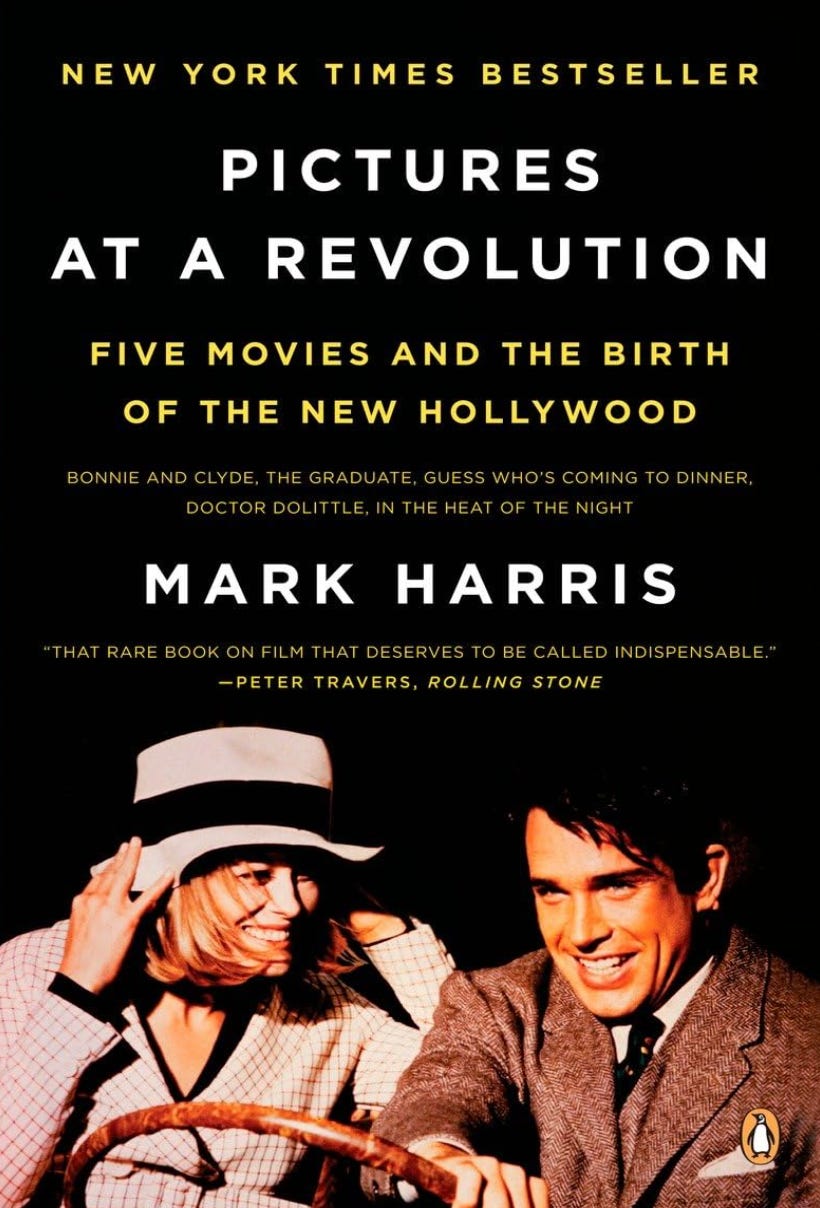

Speaking of pictures…I did the following interview a week before the election. It’s with culture journalist Mark Harris, who is the author of some great books about American film, including Pictures at a Revolution, a deep cultural dive into the five films nominated for Best Picture in the seismic year of 1967…

…Five Came Back, about WWII-era Hollywood directors, and a biography of director Mike Nichols. I’ve known Mark and his writing for a while, so after I read this amazing recent essay of his in The New York Times’ T magazine about the cultural phenomenon of the “daddy”…

…I asked him if he’d talk to me for Caftan, not only about daddyism but about some other things I’m fascinated in, such as key depictions of gays in films and TV over the decades, at what point in pop culture images of gay men went from mocking and almost inevitably stereotypically effete to actually hot, and why gay men have long worshiped certain women of culture both high (Maria Callas, Meryl Streep) and low (all the Real Housewives). By the way, I have recently been obsessed with this clip of pretty obviously gay young guys waiting in line for days in 1965 to buy tickets to Callas’ return to the Met. (I have such a crush on the second one who speaks, especially when his eyes bug out in fanboydom.)

Mark, 60, is such an easygoing and affable guy and we ended up talking for more than two hours the day before Halloween, leading to what I consider a kind of gold-standard Caftan interview, because it’s about stuff somewhat unique to us older queens (such as Faye Dunaway’s career trajectory) but elevated by Mark’s professional-grade interpretation and insights. It’s an unusual Caftan interview because it’s not really about Mark, until the end when, as I promised him I would, I ask him some intrusive questions about his 26-year relationship with the playwright and screenwriter Tony Kushner (yes, of Angels in America fame). You can see how he answers.

So I hope you enjoy it. I consider it a bit of gay cultural escapism at a moment when I think people are torn between wanting to just retreat into comforting personal interests and wondering how to keep up on politics, and even engage, without losing one’s mind. As ever, I appreciate everyone’s support, and, as ever, I’ll ask free subscribers to 1. consider upgrading to paid for only $5 a month and 2. at least tell folks about Caftan by posting it on your socials if you’re on there, or simply by old fashioned word of mouth.

And please please drop me a line and let me know what you think about Caftan and who you think I should try to get for talks going forward. xTim

Mark, thanks so much for talking today. How are you?

Mark: Pretty good. I don’t know that I define being pretty good the way I did 25 years ago but I’m good.

Where do you and Tony live again?

Mark: On the Upper West Side, right near Lincoln Center.

I love that. Very iconic.

Mark: Yeah, we’re nicely between Central Park and Riverside Park and both of those are good for dog walking. We have one dog—Loofah. A 12-year-old poodle. That’s her name because she’s little and looks like something you could use to scrub something.

I hope you don’t use her in the shower.

Mark: We do not. We moved into this apartment 22 or so years ago and I used to complain bitterly about living on the UWS, which is where I grew up. It feels like the city’s largest retirement community. But it’s been humbling to become one of those people. I’m now squarely in that demographic. Things that annoyed the shit out of me 20 years ago now seem like conveniences, like it’s quiet and easy to get things delivered and there’s a lot of drugstores.

Mark, let’s start by talking about your daddy article. I love it—it’s so deeply thought and I want to unpack it with you. Let’s start here: When I was in my twenties in the nineties, I don’t really remember daddy being a thing. When I was 30, I had a roommate who was about 24 and obsessed with daddies and it struck me as very niche. I asked him once, “How old is a daddy?” and he was like, “35.” [we both laugh] I was like, “That’s not a daddy.” But to the point of your piece, it’s such a huge buzzword these days. Why do you think it exploded in the last five or ten years?

Mark: I agree, I used to think being into daddies was a very specific kink but not a whole cultural thing. But I honestly remember being 24 years old and thinking that everyone age 37 to death was, like, old.

It’s funny you say that. When I was 24 or 25, I was attracted to older guys all the time. But weirdly, I never thought about how old they actually were. They could’ve been in their thirties, forties, fifties, but to me they were just older. And now, at 55, I feel like I’m so conscious of what decade someone is in and what that means.

Mark: Same, right. The guys I were attracted to were generally guys my own age, or close to it, and people who were older were all the same. Some of them were attractive and some were not, but I didn’t narrow it down more than that.

Right. Also, in retrospect, I realize that I was daddymatized and it so much had to do with my relationship with my own father, but I didn’t have language for it. I couldn’t really tell you why I was drawn to these older men and now in retrospect it’s so clear that I had daddy issues. But you didn’t?

Mark: Well, maybe I did, but that took a long time to unpack. But to your question of why the daddy boom now, it’s so hard to say. I’m working on a book now about the last 80 years of pop culture as it specifically relates to gay people and the gay rights movement.

That sounds really amazing actually.

Mark: One thing I keep realizing over and over is that there are aspects of the history of gay men that move phenomenally quickly and then others on parallel timelines that move incredibly slowly. And I think maybe the daddy culture thing is one of those that moves slowly. I think of it partly in relation to HIV and AIDS, and I think about the several generations of gay men who died. I mean, I’m 60 and I’m still a little too young to have been right in the center of that loss. Most of the people who died in the initial horrible years, say 1982 to 1996, ranged from a little to a lot older than I was. You missed that group too.

Yeah, I’ve always said that I felt like, not coming to NYC until age 22 in 1991, I was the second wave, the safe-sex generation where we weren’t blindsided by AIDS but came of age knowing what it was and how to prevent it. And there was a great deal of fear and wariness but we weren’t clobbered by it in the same way. Many of us ended up getting HIV but it was largely right before or after the effective regimens started coming out in 1996 and beyond.

Mark: Right. And so culturally there were several generations of gay men who did not have the opportunity to watch gay men get older healthily—or to develop interesting feelings, including feelings of attraction, to older gay men. We associated aging with illness and death for so long, and it was also intermingled with this whole self-loathing a lot of gay men had, and still have, about getting older. There’s always been this strain in gay culture that being old is terrible and embarrassing. It’s taken a really long time, given those two things, for the culture to sort itself out and for there to be a lot of gay men around who are getting older and who are vital and interesting and hot. And for younger gay men to get used to the idea that that’s the world now.

When you say “interesting feelings,” what do you mean by it?

Mark: Well, I think we went through several phases, the first being when there weren’t a lot of older gay men around, then there were but you couldn’t be sure if they were going to stay around. And then I think there was this kind of condescending phase you started to see with the rise of social media, like, “Elder gays have a lot to teach us!” Like we’re all fucking Yoda. We can’t be sexual beings but occasionally some pearl of wisdom would drop from our ancient mouths, or we could explain some piece of pop culture that happened before 2006.

I feel like it’s only been fairly recently that we’ve gotten maybe past that and there’s this big pool of older gay men in every sort of area of celebrity and achievement now. Once that happens, it makes room for other questions to be asked, like, “Okay, well, what if I’m the kind of young guy who is sexually attracted to older men? What kind of older man am I attracted to?” And connected to that, “What kind of older man do I want to be?” I don’t think there was a lot of space for young gay men to consider either older gay men or getting older themselves until fairly recently.

Right, yeah. So I love when you say in the piece that this moment is “both deeply suspect and kind of glorious.” So, do you think you’re a daddy?

Mark: [laughs] Um, I mean— [pause] I don’t think I’ve thought of myself as a daddy on my own, but I’ve had a few interactions in recent years with younger gay men where I thought, “Well, it doesn’t matter if I think I’m a daddy because they think I’m a daddy.” If I’m talking to a 35-year-old gay man and he’s behaving a certain way, it’s, “Oh, yeah, he sees me as a daddy.” I’ll take it—I’m fine with it. I have a lot of friends close to my own age and if you’re sitting around with them, the idea of us all being daddies isn’t necessarily going to come up. Even though there are certain older guys I know who’ve consciously cultivated it, who see being a daddy as not even a style gesture so much as a whole persona, who want to hang out with guys who will see them as a daddy and call them daddy and all that. That’s not me.

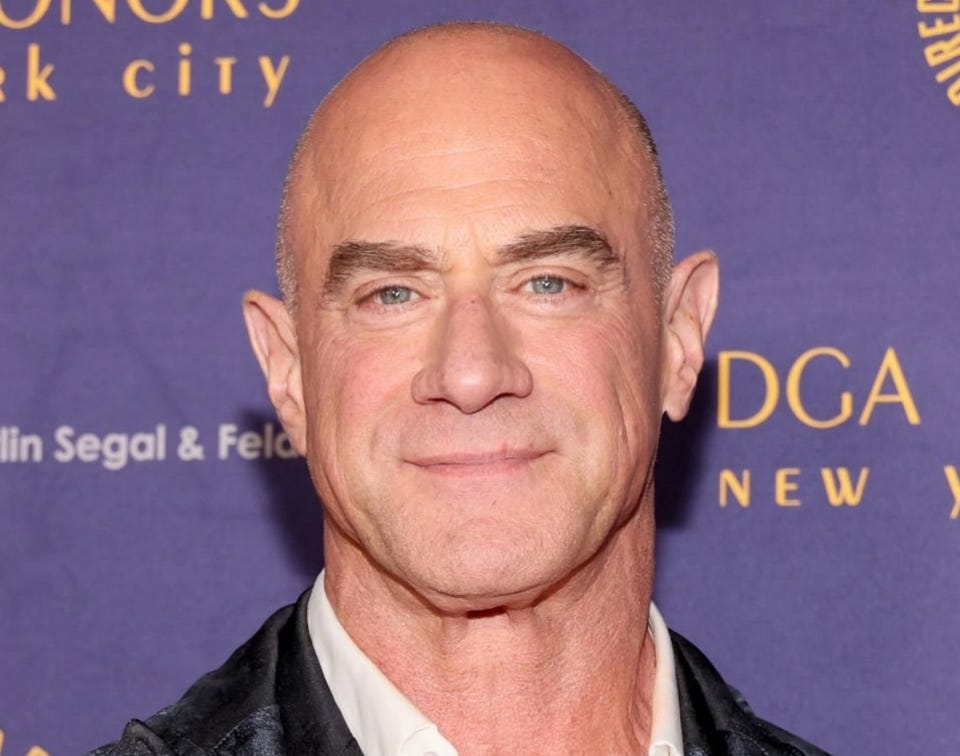

Right. You characterize the archetypal daddy in the piece so well—this kind of cool, smirky, self-assured—that sort of ironic half-smirk that I definitely associate with Chris Meloni, who seems to have that vibe down.

So these friends of yours—they cultivate that affect?

Mark: Yes. I think Chris Meloni is a perfect example. I am not Chris Meloni in any way. [laughs] But yeah, I think there’s a kind of authoritative, challenging, as you said slightly smirky, slightly grizzled quality that is part of one of the many daddy personas. Even though you can have none of those things and still be a daddy. Like, I think Colman Domingo is very, very daddyish and he’s not like Chris Meloni at all.

There are different kinds of daddies. But one thing they all have in common is a kind of unforced sexual confidence that daddies have. You should look entirely comfortable in your own skin, in you own clothes, with your age. You can’t be a daddy unless you are very, very comfortable with where you are on the timeline. If you look like you’re trying to look younger than you are, you’re not a daddy.